Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

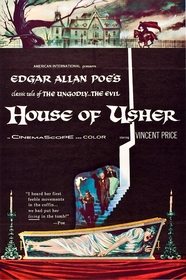

Fall of the House of Usher (1960)

In the early 1960s, low-budget filmmaker Roger Corman convinced American International Pictures to give him enough money to fund a movie based on Edgar Allan Poe's "Fall of the House of Usher." The film would be entirely in color, a first for AIP, and would also feature something unheard of for such a low budget studio: a star.

Thus began the fruitful collaboration between Corman, AIP, and Vincent Price, working together to bring out a cleverly produced series of Poe movies. The first, The Fall of the House of Usher (or simply House of Usher), is often considered the best and for good reason. Although Corman's skills as a director had not yet completely matured, the adaptation was solid, both in concept and execution.

The film opens on Philip Winthrop (Mark Damon) riding through a twisted, burned-out forest. His destination is the titular house, where he finds himself most unwelcome. Despite his efforts to whisk his fianceé Madeline (Myrna Fahey) away from the clutches of her tragic, haunted brother Roderick (Vincent Price), Philip finds himself stymied. In order to save his beloved, he must unravel why Roderick believes the family line is cursed, and how Madeline fits into this obsession.

Corman and screenwriter Richard Matheson take a strongly Freudian approach to the film. The setting and events within them are exaggerated, stylized. Overall, they're more in line with Philip's perceptions than the actual truth. Roderick is an opponent for Madeline's affection, and that affection is translated into subtle sexual ardor (which may very well exist outside of Philip's psyche as well). Madeline seems more intimate with Roderick than she does with Philip, more willing to bend to her brother's will than that of her betrothed. Corman wisely plays the incest as wholly subtextual, and therefore it's easy to dismiss by those who simply cannot tolerate the concept.

Atmosphere is the key element to enjoying Usher. Corman had to sell the picture to AIP on the concept that the house itself was the monster, and every effort is made to stay true to this. From the fog that swirls at the base of the house to the strange paintings hanging on the walls, the house reeks of menace. Sometimes this is used for some cheap thrills (take the silly falling chandelier, for instance), but mostly it's an effective tool to keep a sense of danger prevalent throughout the film.

Opulent sets abound here, courtesy of production designer Daniel Haller. Given a very limited budget, Haller put together an ornate look for the film, mostly by reusing and rearranging. There's one set used for at least three different bedrooms, the elements swapped out or rearranged so as to appear to be a completely different for each distinct location. Haller was able to keep the majority of the flats, and reused them for later Poe films (therefore, the sets became more elaborate as the cycle went on).

Vincent Price is, perhaps, the most effective piece of atmosphere in the movie. It is his talent to portray haunted and tortured twisted together into a single emotion. His voice exudes horror, both given and received. He rarely speaks in anything stronger than a whisper, and yet his presences dominates the film as if Roderick Usher were the very embodiment of the Usher curse.

Usher begins a trend that would plague many of the later films in the Poe cycle -- a lackluster male protagonist. Damon seems to have been cast more for his looks than his acting ability. He gapes and waggles, brutalizes his surroundings, and generally makes an ass of himself. Subtlety, thy name be not Mark Damon.

Corman is less sure of himself here than he would be in his next Poe film, Pit and the Pendulum. His camera work in Usher is more staid, less willing to work outside the box of the usual shots. However, his work is strong -- all those years of toiling in B- and Z-grade flicks pay off. He displays a mastery of depth of field, and his pacing is always solid.

Unfortunately for the film, it's in the very wide aspect ratio of 2.35:1. This is a very difficult ratio to film horror in, as the action tends to be held at a distance, rather than being intimate, invading. John Carpenter is one of the very few who have ever really used 2.35:1 to effectively convey terror and suspense. Corman is far too untrained at it; pointless dead space frequently mars the frame. Occasionally, Usher comes off as a gothic costume drama rather than a chilling horror picture.

Later films in the cycle would improve upon Usher's individual elements - the direction would be more assured, the sets more lavish, the acting better tempered. However, Usher is better than the sum of its parts. Corman manages to overcome the flaws through sheer power of will. Thus, the first film in the Poe cycle manages to be one of the best.

Trivia:

The footage of the house burning (which was on-site footage from a real burning tragedy) would be used in many later Corman productions.