Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

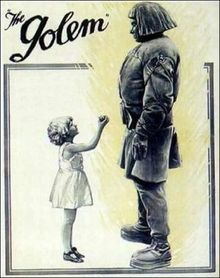

The Golem (1920)

Emanating from Jewish folklore, the legend of the “golem” has transfixed audiences for centuries. Although when used pejoratively the word “golem” describes a moronic person easily manipulated, the word often refers to any mythical creature animated from inanimate materials such as clay, sand, or stone.

One of the most popular “golems” appears in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy. Spelled “Gollum,” Tolkien’s character shares similarities with creatures that haunted Jewish legends, particularly the golem featured in director Paul Wegener’s 1920 silent classic, The Golem. Both suffer from split personalities and possess hybrid traits: Gollum is part human, part frog, fish, etc.; many Jewish golems, including Wegener’s, are monsters made of inanimate objects that carry human traits. Both have been damned or punished, and in both instances, the creatures start well intentioned but transform into evil beings, usually due to gluttony, greed, wrath, envy, or pride. Thus, they are morally “gray,” and like Wegener’s monster, Tolkien’s has often been depicted as gray in color to symbolize this amorality, most notably in Peter Jackson’s recent films.

Wegener’s classic is based on the Jewish legend from the late 16th century and features a grayish clay figure animated to protect Prague Jews living in the ghettos. His source material was Gustav Meyrink’s 1915 novel, Der Golem, which is derived from Judah Low ben Bezalel’s tales (a.k.a. Rabbi Loew). Wegener made three versions of this popular legend: The Golem (1915), The Golem and the Dancer (1917), and this film, which is subtitled "How He Came into the World." Unfortunately, the earlier two versions have been lost.

It’s 16th Century Prague, and the mystical alchemist and scientist Rabbi Loew deciphers a constellation and learns that trouble looms for the city’s Jews. Soon thereafter, the Emperor banishes them from the city because of their displays of “black magic” and the dangers they present the Christian majority. Loew creates the golem, with the help of the deity Astaroth, also known as the Prince of Hell, and a magical amulet which, when placed on the golem’s chest, brings him to life, but when removed renders the monster lifeless.

Due to his supernatural prowess, Loew is invited to the emperor’s palace to entertain the people during a festival, but when they laugh at the rabbi’s depiction of his people’s exodus, the palace crumbles. The golem saves the emperor and his citizens by holding up the crumbling roof. After this heavy lifting, Loew renders the golem lifeless, but his assistant, Famulus, revives him out of jealousy. Loew’s daughter, Miriam, loves one of the emperor’s courtiers, but Famulus doesn’t approve. The golem runs amok, burning buildings, tossing people off towers, and eventually finds itself in a playground where the local children ironically confront him.

Who exactly is Rabbi Loew? A cabalist scholar, Loew, who lived in Prague from 1513-1609, is no stranger to narrative art. Disney’s “The Sorcerer's Apprentice” sequence in Fantasia (1940) is rumored to be drawn from the rabbi’s life; Nobel Peace Prize-winning author Elie Wiesel has written his own account of him; and the rabbi appears in an important subplot in Michael Chabon's Pulitzer Prize-winning 2000 novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. A statue of the rabbi stands in Prague near the famous Jewish ghetto, and locals refer to him as “The Exalted One”.

Wegener co-directed the first version of his golem cycle with screenwriter Henrik Galeen, who penned the screenplay for Nosferatu, and Wegener played the role of the monster in all three versions. Wegener hired Galeen again to write The Golem’s script, and Carl Boese helped direct this third installment. Nevertheless, most critics consider Wegener the film’s primary creative architect.

Wegener’s expressionless portrayal of the golem is controlled and effective, and ultimately, culminates his vision for the cycle. At times, the golem seems a giant gray robot; during others, it conjures memories of Frankenstein with his enormous boots and tall, lumbering gait and frame. Throughout, Wegener doesn’t blink an eye, and his neurotically stoic performance is commendable.

That the golem is made of clay suggests his presence is a natural extension of Loew’s psyche. If we’re all composed from Earth, man and beast alike, the golem represents that part of our soul that screams for protection from a cruel world. He is a paternalistic superego fueled by a sense of righteousness that limits harmful powers, such as the emperor’s, which exist unchecked. His vengeance is unfailing and automatic, and the villagers are more mesmerized by his presence than scared.

Golems have appeared in various forms throughout global popular culture. French, Japanese, Polish, and Czech versions of the legend have been produced on film. In America, the myth has appeared numerous times; more notably are in a Dean Koontz novel, Dragon Tears; an episode on The Simpsons, “Treehouse of Horror XVII”; and The X-Files episode “Kaddish”.

Interestingly, Wegener’s initial inspiration for the film was sparked by Edgar Allan Poe’s famous short story “William Wilson,” about a person suffering from multiple personalities. The film carries the theme of dual personalities well, as duplicity infiltrates many scenes. The Jewish people are tucked away in a cramped ghetto, removed from mainstream Prague; Miriam and her beau hide their love behind closed doors; Loew creates a monster behind his lab’s façade; and Famulus deceives his master. In a sense, since the film fundamentally addresses the horrors of anti-Semitism and the pain associated with class division, the film’s treatment of duality is best understood as a reflection of the damaging and dividing psychological stress racism and poverty cause. Power is determined by demographics, the film suggests, and due to our social class, religion, rank, or race, we have certain “places” in society to occupy; when we defy that order and trespass those boundaries, chaos looms.

Cinematographer Karl Freund, who later photographed two other German Expressionist classics: Fritz Lang's Metropolis and F.W. Murnau's The Last Laugh, displays his prowess early. The film opens in darkness as dimly or candle lit scenes establish the drama. The set is plastered with intricately designed geometries, which convey confusion and separate, meticulously delineated spaces. Everyone and everything is confined visually to squares, triangles, or circles. In contrast, as the camera photographs the golem during its romps toward the village, stark skies and empty panoramas fill the screen. Interestingly, Freund later immigrated to the United States and shot the popular television show I Love Lucy, a dramatic departure from his German expressionist roots.

Although The Golem is mostly free of Jewish stereotypes, such as the myth that Jews control everything (Loew controls little, particularly his own creation), during World War II, Wegener worked for and helped the Nazis produce propaganda films. Later, he earned Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels’s praises. Ironically, the film shines a spotlight on anti-Semitism because Wegener’s Jews are constantly treated as quintessential, easily disposable “Others”. While the golem saves them, their future, like its, is a fragile one, and their safety is temporal. Critics have read the film as anti-Semitic, arguing that a Christian “spin” on the legend renders Loew’s people punished for their hubris. How dare he invoke the heavens for his people’s provincial gains, the argument goes.

Among its ardent followers, the film has been vulnerable to unique debates. Is it genuinely a German expressionist film? Hans Poelzig’s set designs would suggest yes, but those sets convey more a sense of visual grandeur than any complex, character-based psychological traumas. In fact, the characterization of the film’s central players is not detailed, and subsequently, some characters are flat and shallow. Famulus’s motivations for reviving the golem warrant further development, and Miriam is too one-dimensional. Given the emperor’s status, his character also deserves more attention.

Is it more a prequel to Wegener’s original or a remake of the 1915 film? That’s a harder question to answer, and having not seen the original, I simply cannot engage in that popular debate. Is it even a horror film? Barely. The film’s pace is slow, and it’s not scary for early silent “horror” film standards. Films such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Nosferatu, The Phantom of the Opera, M, and Vampyr are much creepier. However, enough suspense exists to at least warrant consideration in the horror canon, and the film’s pedigree helped establish themes central to the genre including its infatuations with mad scientists and Frankenstein-like creations. Nevertheless, the film reflects more clearly the social tensions of its time and works better as a thrilling drama with a heavy dose of cultural history than a “horror” film.

The film’s special effects, musical score, and editing make it a noteworthy early installment in the horror genre. However, it takes a back seat when compared to its peers. Mainly die-hard fans of horror will appreciate this one.

This review is part of German Horror Week, the third of five celebrations of international horror done for our Shocktober 2008 event.

Fantastic article! Thank you!

Fantastic article! Thank you!

Brilliant review! Did a

Brilliant review! Did a video review of Der Golem as well. It's a bit irreverent, but I love classic horror.

Thanks very much for this.

HS