Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

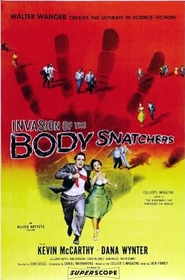

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

No film captures the anxieties of an entire decade of American history better than Don Siegel's Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Shot in only 23 days at a cost of roughly $420,000, Invasion is based on a Jack Finney serial story published in Colliers Magazine in 1954. A year later, the novel "The Body Snatchers" was released; a year after, the film, which Walter Wanger produced, emerged as one of the best sci-fi thrillers of the 1950s.

And as one of the great cult B-movie classics, Invasion has long fascinated Hollywood insiders enough to warrant two remakes. The first was released in 1978 and featured Donald Sutherland; Abel Ferrara directed the second, which was titled Body Snatchers and released in 1993. While both films hold merit, particularly the 1978 version, which some consider better than the original (certainly begs for a healthy debate), the original transcends the vast majority of its peers from the 50s.

The film is also riddled with legendary production anecdotes. Wanger produced Invasion shortly after he was released from jail for attempted murder; he was incarcerated for a four-month stint that involved a shooting incident between him and his wife's lover. Wanger's wife was Joan Bennet of Dark Shadows fame. Daniel Mainwaring, who also penned the script for arguably the greatest film noir ever, Out of the Past, wrote the screenplay, although Sam Peckinpah assisted. However, the degree of Peckinpah's assistance has been questioned for years. Peckinpah did have a cameo in the film (he plays the meter reader) and was the dialogue coach, but Mainwaring and others disputed his writing credits so fervently that they planned to file an official complaint with the Writers Guild of America. Ultimately, they didn't. Nevertheless, when the maverick director died in 1984, several obituaries included the film in their writing credits section.

After a professional conference, hometown physician Miles Bennell returns home to Santa Mira to encounter a waiting list of patients. Many of the residents are feeling odd and suffering from strange, inexplicable sensations. Some are apparently "not themselves," at least according to relatives. Bennell investigates and finds one victim morphing into a replica of his friend. Soon, Bennell, who throughout the movie courts his love interest, Becky Driscoll, discovers unusual "sea-pods" that incubate these newly morphed souls. Eventually, the entire town succumbs to the "disease," and Miles and Becky become the final guardians of humanity who must run for their lives to preserve civilization.

Invasion's timeless appeal lies in the fact that every generation and culture can see its own vices, flaws, and follies in the sickness and hysteria that plague Santa Mira. The film is an exercise in allegory, and the narrative is constructed so that virtually every component of the plot can be interpreted as symbol. No social, cultural, or political dilemma from the 1950s is spared. Although Siegel has often challenged such interpretations, it is difficult not to see Santa Mira's "group think" as representing the Red Scare fears of Communist beliefs and the subsequent hysteria these beliefs produced as symbolizing McCarthyism. The film also can be read as an indictment of the conservative, conformist culture of the 1950s; the general fears of death stirred by the atomic bomb; the fear of science and its many discoveries; the American government; consumer culture; and the dawning age of space travel. Throughout the film, Bennell, passionately played by Kevin McCarthy (how ironic!), offers mini-soliloquies addressing many traditional, nationalistic beliefs about these topics. In the last 50 years, these symbolic representations have become the topic of many essays written by film professors and students.

The courtship between Bennell and Driscoll also works in further emphasizing the many cultural and social restraints inherent in 1950s America. And in many ways, those restraints mirror the intangible restraints posed by the pods and the hysteria they create. Bennell clearly wants to express his love to Driscoll, but he must do so secretly, similar to the way the couple must hide during the latter half of the film. Driscoll's father functions as a nemesis to their relationship, as most fathers did in the 1950s, and his adversarial nature is further amplified when he becomes one of the leading Others whose personality the pods steal. In a sense, the struggle to consummate their love is a microcosm of the drama created by the invaders.

Carmen Dragon's musical score is as haunting as the narrative. The atonal piano chords infiltrate virtually every scene of the film in the same way the "disease" infects Santa Mira. Tense, eerie, and unexpected, his soundtrack adds another layer of tension to an already nerve-wracking film. His work has also been featured in television shows including The X-Files and Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Amazingly, no monsters ever appear in Invasion, other than the pods, which hardly qualify, nor does anyone actually die on screen. Yet the film does wonders in creating dread. That is partially due to the way it borrows from the many conventions of film noir, a genre in full swing by 1956. The voice-over breathes a looming sense of doom into the narrative, and the prologue, which along with the epilogue was added after the film's original release, adds a sense of fatalism. We know we are headed for a train wreck. The dimly lit scenes that permeate the film and the stark black-and-white photography add another layer of confusion to the paranoia. And the night-for-night shooting that occurs in the film's second half clearly adds yet another layer of fear and uncertainty.

Invasion is a must see for any film buff of 1950s sci-fi thrillers, and the original should be seen if readers have any interest in the other two versions. It is not only a great, suspenseful film, but Invasion also serves as a unique lesson in American social history.

Trivia:

Sam Peckinpah did uncredited script work. He has a cameo as a meter reader.

A 1979 re-release intended to cash in on the Donald Sutherland remake cut out the emergency room prologue and epilouge with Whit Bissell.