Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

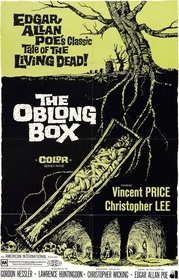

The Oblong Box (1969)

After Roger Corman ended his cycle of Edgar Allan Poe-based films with 1965’s Tomb of Ligeia, production company American-International tried to keep it alive with different directors. One such director was former “Alfred Hitchcock Hour” associate producer Gordon Hessler, whose Poe cycle debut was the in-name-only adaptation of The Oblong Box. In Box, Hessler takes a lackluster script and uses a little ingenuity to polish it up visually, resulting in a very good-looking but hollow film.

In a plot that bears more similarity to Rudyard Kipling’s “The Mark of the Beast” than Poe's short story, Julian Markham (Vincent Price) returns from his African plantation accompanied by his brother Edward, who is in a rather altered condition. It seems that an act of vengeance by an African tribe left Edward’s face disfigured and his mind unhinged. Julian keeps Edward locked up for the safety of the family name, until Edward fakes his death in a bid to escape. Unfortunately, Julian gets him in a coffin too quickly, and Edward is buried. His grave is robbed and the body brought to Dr. Neuhart (Christopher Lee), who discovers that Edward is quite alive when the man tries to throttle him. Free of his brother and hiding his gruesome features behind a crimson hood, Edward seeks revenge on all those who wronged him… and any person who gets in his way.

From a writing standpoint, The Oblong Box is a bloated affair. The screenplay by Lawrence Huntington (The Vulture) attempts to track too many plot threads, picking up protagonists and dropping them as the mood suits. To begin with, we follow Julian, but we forget him in favor of the Markham lawyer, Samuel Trench (Peter Arne). Trench, however, turns out to be a scoundrel, and, as if to acknowledge this, the focus shifts to the tragically mad Edward. By the film’s conclusion, we’ve doubled back to Julian, the original protagonist.

Further, it seems that every time Huntington tries to move the plot forward, he must introduce two or three new characters to accommodate it. Towards the end, the film is so flush with people that they cannot help but bump into each other in random ways, occasionally pushing forward the plot, but more often than not padding it. What is the necessity, for instance, of following Inspector Hawthorne (Ivor Dean) so closely if his character is ultimately going to completely disappear, his entire effect a utilitarian one that could’ve been served in three lines instead of three scenes.

All these additional subplots and digressions do a disservice to the audience’s experience. None of the characters are sufficiently developed for our sympathy, and that's not even the most concerning problem. The biggest let-down is that a significant moment in horror history is thoroughly undercut. The Oblong Box marks the first time that the actors Vincent Price and Christopher Lee appear together in a film. However, they are only afforded one scene together, and when it comes, it is a disappointment. The film has wasted so much time on inconsequential matters that Lee, whose character is dying as Price’s rushes in, only has time to groan out a word that doesn’t even make sense in the context of the plot. That’s it. That’s the brilliant repartee afforded two legends of horror – a groan.

Hessler and cinematographer John Coquillon (who would work with Hessler on two future projects – Scream and Scream Again and Cry of the Banshee) do what they can to at least make each scene work visually. The movie opens in an African hut (or a set at Shepperton Studios done up like an African hut) during the ritual that disfigures Edward. Hessler frequently relies on shooting from Edward’s POV, using a lens that puts the face of the African witch doctor almost through the cinema screen. It’s intrusive, effectively communicating Edward’s terror of both his unknown punishment and the alien (to him) culture that is enforcing it. Once the action moves to England, Hessler continues to use the extreme POV to represent Edward for a while, this time to show his warped state of mind.

To Coquillon’s credit, colors throughout the film are rich and the lighting moody. Whenever Edward wears his hood, it is photographed very specifically to emphasize its blood-red color and velvet texture. The Oblong Box frequently likes to emphasize the baser things in life, and Coquillon keeps the photography properly sordid in those scenes. In a bawdy tavern/bordello sequence, shots are kept tight to bosom-flesh, leg-flesh, or whatever other comely woman-flesh happens to wander on screen. Murders are also up close and personal, specifically emphasizing through the framing and lighting exactly where Edward’s knife is meant to have punctured flesh (Occasionally, the shot is too close – in at least one instance, you can see the special effects knife squirt out blood before it’s even touched to skin.).

Despite his skill for visual splendor, Hessler cannot create a good sense of pacing, exacerbating the problems of the unfocused script. Frequently scenes run on too long, especially those involving “selling points” of the film, like sex and violence. The aforementioned bordello sequence significantly outlives its welcome, to the point where I began checking out the background extras and wondering how much they made for their contributions. Later in the film, we come back to the same bordello and watch a knock-down drag-out brawl that has nothing to do with the plot of the film. It’s almost as if Hessler is curious to see what happens after the main characters leave a scene, and thought that as long as there was some action occurring, the audience wouldn’t mind his indulgence. I mind. The end result of Hessler’s bad pacing decisions is that the film feels too long, even at 97 minutes.

Vincent Price, in full beard, gives one of his better performances as Sir Julian Markham. Giving the most sympathetic performance of all the leads in the film, Price overcomes an uneven script that unevenly depicts Julian as both a concerned brother and a manipulative charlatan. Most surprising is Price’s restraint – the actor eschews his usual flourishes for a more buttoned-down approach. Perhaps this is less surprising when one realizes that Price had just come from making Witchfinder General (aka The Conqueror Worm) where director Michael Reeves would stop filming whenever Price’s performance became arch. Whatever the reason, this new, subtler Price is as welcome as the old scenery-muncher.

Christopher Lee, clad in a ridiculous silver wig, does well with a supporting role. His Dr. Neuhart is, as Lee himself puts it, “a good man … gone bad due to his obsession to learn more about the body."1 This obsession puts him in questionable relationships with graverobbers, a blackmailing maid, and finally the insane Edward. Throughout the film, Lee perfectly conveys his annoyance and frustration through shifts in vocal tone and minute facial twitches. Even in small parts, Lee’s devotion to giving his best performance shows why he is one of the great character actors of all time.

Great performances and enticing visuals manage to make The Oblong Box a worthier experience than the awful script would allow. Fans of Price, Lee, or Hessler would do well to seek this one out. Anyone else may be wasting his or her 97 minutes.

- 1. Johnson, Tom, and Mark A. Miller. The Christopher Lee Filmography: All Theatrical Releases, 1948-2003. McFarland & Company, 2004.