Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

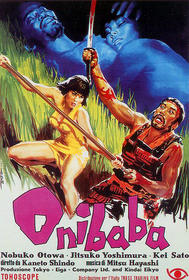

Onibaba (1964)

Our scene opens with two samurai, running through the tall, oppressive reeds. One is wounded, and the other is helping him along. Suddenly, their flight is interrupted, their lives coming to a sudden and grisly end at the points of vicious spears. Their desperation permeates the very opening frames of Onibaba and sets the tone for the entire film. Onibaba is a tale of deceit, murder, sexual frustration, and the monstrosity that lies in the hearts of ordinary people. With such a great story at its core, Onibaba excels by way of great performances, excellent cinematography, and stellar direction.

Onibaba revolves around two women, a mother and her daughter-in-law, who resort to killing samurai and selling their possessions for a living. They meet Hachi, a comrade of the mother’s son and daughter-in-law’s husband. He delivers the terrible news that their loved one is dead, killed as part of the civil war between the feuding noble families. Hachi, no saint himself, also takes part in the slaughter of samurai, at the same time seducing the newly widowed young woman. The grieving mother is overcome with jealousy and insecurity at their new sexual union. This jealousy builds until it consumes her entirely, driving her to desperate, dangerous acts.

It is a simple plot, but one masterfully executed. From the very beginning director Kaneto Shindo builds his movie on brilliant cinematography. The field of tall reeds, the claustrophobic hut the women share, every setting is envisioned with such grim and wonderfully overwhelming atmosphere. Roughly half of the scenes are filmed indoors. These interior shots are mostly composed of the small huts of the villagers. Cramped closed off, the roofs almost always in view of the camera. By using these structures to isolate them physically, the setting reflects the oppression of the peasants in their social standing. The exterior shots are no less claustrophobic. Framing every shot in the swamp with the reeds towering over the characters, Kaneto traps them in their surroundings. The only exterior shots that exhibit any sense of open space are on the waterfront. However, being the site where the women and Hachi drown a pair of samurai, this water is linked not with life, but with death. When you combine these factors with the stark, highly contrasting lighting, everything adds together for what can be simply described as beautiful cinematography.

Even with great direction and cinematography, a film may succeed or fail based on the performances of the actors. In the case of Nobuko Otowa, playing the mother, the acting is pitch perfect for the film. Her careful jealous rage and self-serving attitude, which manifest as a hatred of males coupled with a simultaneous, seemingly contradictory, lust only adds to the sense of desperation and oppression that permeates the film. Later, when she wears a horrible Oni (Japanese demon) mask, which blocks her face entirely, her body language portrays all the emotions she needs. Her performance is not hindered in the least. Similarly, Jitsuko Yoshimura's portrayal of the young woman is also nuanced and wonderful. Hardened by the horrible acts she commits, she still clings to a sense of vulnerability that she can seemingly only achieve by submitting herself sexually to Hachi. It is Yoshimura’s careful handling of her performance that allows these facts to surface, ensuring that we see not a wonton girl, but a woman submitting to sex for the purpose of self-preservation. Rounding out the cast is Kei Sato as Hachi, who provides a brash, strong performance that stands in great contrast to the women. He is rude and crude, yet not a simple male stereotype. In many ways, it is reminiscent of Toshiro Mifune's performance as Kikuchiyo in Seven Samurai. Sato tempers his crudeness with humor and boisterousness, creating what would be the most likable character of the film if not for his rough, overly physical methods of sexual seduction. The entire ensemble does their job well, giving Onibaba a solid foundation on which to create a nearly perfect film.

Onibaba is a classic, not because of its age, but because it is a masterpiece of filmmaking. With brilliant cinematography, wonderful setting, and stellar performances, Onibaba really is a full-package deal. This is a gem, a film for not only the horror enthusiast, but for any film fan. Do yourself a favor, and track down a copy of this as soon as possible.