Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

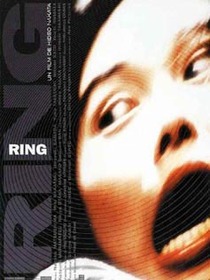

Ring (1998)

Judged on plot alone, Nakata Hideo’s Ring ought to be pretty tame. Indeed, this uniquely compelling cinematic work often comes across, on first description of the story, as a piece of over-the-top Japanese kitsch. The story of a cursed videotape that kills the viewer within seven days ought not to be this scary. Yet it has chilled and awed mainstream Western audiences, and almost single-handedly brought about our current obsession with Japanese horror. Arguably, it has paved the way to mainstream success in the West for the likes of Takashi Miike and others. The point is that the art of terror revolves around context. That old campfire chestnut in which a ghost hunts down the liver stolen by a schoolboy from his now uninhabited corpse looks ridiculous on paper. Yet we all know how scary it was against the crackle of the fire and the screeching of owls in the nighttime. Similarly, the story of a cursed videotape takes on a whole new significance when you find yourself sitting in front of your television and watching that very tape.

In what may be the most tense and hard-to-watch opening scene since Don’t Look Now, Ring begins by bringing us into the realm of the instinctively scary campfire story. Two schoolgirls are trying to scare one another with urban myths. One mentions a strange videotape. It features a woman who stares right out at you. Once you have watched it, the phone rings and a voice says, "You saw it." Within seven days, you die. The other girl appears genuinely scared. Apparently, she has watched such a tape, and that was (yep, you guessed it) exactly seven days ago. The girls laugh it off and continue to enjoy their sleepover. That is, until one of them is suddenly killed, her heart having stopped beating and her face contorted in fear.

Ring’s masterstroke is its ability to make the viewer feel part of the movie. The whole film has the sparse, tensely surreal atmosphere of a fever dream, and draws you into its world by clever, subtle means. The movie is shot so that one would be forgiven for thinking it was not in colour. The film is imbued with muted greys and beiges and punctuated with stark blacks and whites. This adds to the unreality of the experience. The cursed film itself is a masterpiece of edgy surrealism. Black-and-white images flash on the screen, held together by a tenuous but compelling aesthetic (and perhaps logical) cohesion. A woman’s face in an oval mirror, brushing her hair. People crawling over one another in agony. A well. The tension created by this and the moments immediately afterwards when, after a short silence, the phone rings, is breathtaking.

Ring was made in 1998, and has already inspired remakes in both Korea and Hollywood. It has caused a thousand teenagers to phone up their friends after the late-night TV showing just to scare the hell out of them. It has made western viewers sit down and quite happily watch a film with subtitles. This film should bring the viewer hope and motivate filmmakers, for it proves that after all these years, no matter how desensitized and jaded we may have become, it is still possible to make genuinely scary and memorable films which will – no doubt – be hailed as classics for years to come.