Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

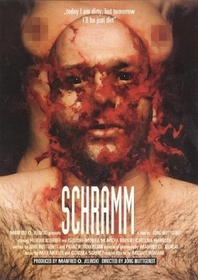

Schramm (1993)

This film was released roughly seven years after Buttgereit's notorious directorial debut, Nekromantik. I didn't care much for his first offering, mainly because I felt it was a copout. The subject material could have freaked just about any audience, mainstream or not, but it was presented in a way that padded the potential force of its blows. I could almost picture Buttgereit softly elbowing a nearby viewer, winking, and saying "Don't worry, it's not like I'm taking this thing seriously. Loosen up." I was not alone in my assessment. Perhaps he caught drift of these collective opinions, and created this film as a way of proving that he could deliver a pure pharmaceutical-grade story of human perversion. I doubt it, though. I haven't had the pleasure of meeting Buttgereit, but he strikes me as a director with a strong individualistic streak. He plays by his own rules, listening to his intuition rather than his critics, and as a result has a way of keeping his fans off-balance as to what to expect next. And I pity the unprepared viewer for Schramm, because the gloves have finally come off.

The film has a surprising complexity and depth, made even more remarkable in its running time of just over an hour. There is no padding to be found here. Every scene holds significance, and one can't help but admire the economy of its approach. Within the first five minutes, we are given a solid basis to proceed on. One, the central character is a serial killer named Lothar Schramm, nicknamed the "Lipstick Killer" by the media. Two, he is critically injured and soon to be dead, lying semiconscious in a pool of white paint and blood. Three, he sustained this injury by falling off of a stepladder in his apartment, painting his wall to hide the arterial sprays of his latest victims. The victims, incidentally, were two Christians spreading the message of salvation on a door-to-door basis. The movie is filled with ironic twists like this, overflowing with merciless black humor, and the most savage twist is saved for the ending shot.

The solid foundation given to the viewer at the beginning of the film is necessary, because the remainder does not follow a linear approach. It takes place in Schramm's mind as his life slips away, using a stream-of-consciousness style designed to be purposely disorienting. Chronological events are scrambled, and I found myself continuously speculating whether his memories were real or figments of his imagination and dreams. In other words, welcome to his world.

It is not a pleasant world to be in. On the outside, Schramm presents as an average-looking middle-aged cab driver, someone you wouldn't give a second glance. He blends in. He has a low-key approach, soft-spoken and a bit awkward when it comes to social interactions. But once we pass through this exterior, the facts are quickly made clear. This man is capable of shifting into unprovoked homicidal rage within seconds. He is suffering from a severe psychotic disorder, and his sexual needs go far beyond the pale. He isn't completely disconnected from reality, and he is not legally insane. He knows enough to paint over incriminating bloodstains. But he is prone to terrifying hallucinations and nightmares that indicate a deep-seated hatred and fear of women, as well as himself. He has a good acquaintance with a prostitute who lives across the hall. And while he dreams of having an ideal and romanticized relationship with this woman, the reality falls short of the fantasy. Each exists to use the other, mostly in trivial ways. One of Schramm's ways is far from trivial.

Schramm came out within a year or two of Natural Born Killers, Kalifornia, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, and Copycat, films that also offered insights and commentary on the psychology of mass murderers. It was a hot media topic, and the recently uncovered exploits of Jeffrey Dahmer were front-page news. If memory serves, some company had even marketed a line of serial killer trading cards. I found myself wondering what Buttgereit's feelings were towards this character, as well as the subject matter in general.

These speculations may be answered by a scene midway through the film, where Schramm is escorting his female neighbor home through a public park. Abruptly the camera shifts away from the couple to a man sitting under a tree, who then shoots himself in the head. The cinematography of this shot separates itself from the rest of the movie entirely. It is shot in black and white with a handheld camera and the cold objectivity of live-action news footage.

I gave a lot of thought to this segment, the potential meaning that it carried in a lean film with no padding. I was left with the conclusion that Schramm had at least some insight into his actions, along with the capability to make choices of his own free will. Suicide was one potential option that could have saved further lives. More preferable choices would have involved turning himself in, seeking help for his psychosis, finding a controlled environment where he could do no additional harm. Yet he chose to continue his current path, and only a random accident put an end to it. Although Buttgereit created this character, I doubt that he cares much for him. And as he illustrates in one closing scene, neither does God.