Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

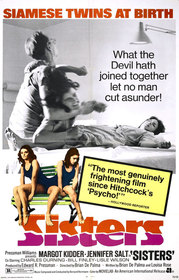

Sisters (1973)

Sisters is a pulpy, Hitchcockian first excursion into the subjects of voyeurism and sexual horror by then unknown director Brian DePalma. Released midway through the period (1968 - 1978) that I consider to be the golden age of the modern American horror film, it does not share the rarified air of classics like Night of the Living Dead or Texas Chain Saw Massacre. But Sisters has enough of its own creative juice to make it very much worth a look.

A chance romantic encounter between businessman Philip Woode (Lisle Wilson) and model Danielle Breton (Margot Kidder) ends in Philip's brutal murder at her Staten Island apartment. The perpetrator apparently is Danielle's separated Siamese twin sister, Dominique. A young reporter, Grace Collier (Jennifer Salt), witnesses the crime from her apartment window. She alerts the authorities but by the time they show up Danielle and her ex-husband Emil (William Finley) have cleaned up the crime scene and hidden the body in the sofa-bed. Determined to find the truth, she investigates on her own and discovers a back story even more disturbing than the murder itself.

Sisters' style is all about subjectivity. In fact a real strength of Sisters is DePalma's unique flair for blurring reality for dramatic effect. The opening credits sequence (which can be viewed at http://artofthetitle.com/2008/07/23/tension-in-title-sequences) is a calling card for this approach. The visuals consist of a series of photographs of human fetuses as you might see in a "Mystery of Life" coffee table book. However, when paired with Bernard Herrmann's discordant four note theme and over the top orchestration those unborn babies start to look, well, scary. All that is missing is a children's choir chanting, "Sisters! Sisters!" DePalma tells us that we are in a horror movie, but more to the point, this is his horror movie.

As the story begins DePalma cleverly introduces the theme of voyeurism by setting a trap for the audience. We are introduced to Danielle and Philip in a rather sensitive situation where Philip (and the audience) are enticed to act as voyeurs. Just before the payoff DePalma pulls back to reveal a cheerful MC and energetic studio audience. The scene was a set up for a TV game show called, "Peeping Toms". The joke is on us, but DePalma is also showing that we are all naturally voyeuristic. Later on the persistent Grace discovers a short news film about the twin sisters. As we watch with Grace, we see sensationalized footage of other Siamese Twins and a chilling Herrmann string accompaniment blended with the story of Dominique and Danielle. It's odd that I did not notice the soundtrack until later viewings. This is because we willingly accept and react to this "documentary" story as a horror movie within a horror movie. In the world of Sisters, a seemingly real situation can turn into a game show and a news story can play as a horror movie, depending on the effect DePalma is trying to achieve.

Another stylistic element that stands out in Sisters is the dynamic created between the two main female characters, Grace and Danielle. A product of the times, Grace is a politically conscious and ambitious young woman. This makes it all the more frustrating when almost no one takes her seriously. The police assume that Grace is just looking for a chance to discredit their procedures in her column. And in scenes that are quite funny, Grace's mom wonders aloud if her daughter's constant agitation about her "little job" is being caused by diet pills. Even rent-a-detective Joseph Larch (Charles Durning), from the Brooklyn Institute of Modern Investigation, treats Grace as a buttinski at her own investigation, quashing her ideas at every turn. Contrast this with the pliant, demurely sexy Danielle. As Grace is trying to break away from the constraints placed by family and male authority figures, Danielle seems to actively seek passive normalcy and specifically male approval. It is perhaps significant that the only interaction Danielle has with another woman in the entire film is with her opposite, Grace during the search of her apartment. This will come full circle later when, during a series of hallucinations, the marginalized Grace will become the other, "abnormal" twin, Dominique.

The previous examples show a creative director starting to find his own voice. However, we must consider another voice that is a significant influence on Sisters. Whether you think DePalma's horror/thriller films are inventive homages or blatant plagiarism, the impact of Alfred Hitchcock on DePalma is undeniable. You can have a terrific drinking game while watching Sisters as you check off each Hitchcock reference. A main sympathetic character gets killed in the first half of the film (Psycho), the overriding theme of voyeurism (Rear Window), hiding the victim's body in plain sight of the authorities (Rope), a young female forced to solve the mystery because nobody believes her story that a crime has occurred (The Lady Vanishes), the list goes on. However, we should avoid the temptation to dismiss Brian DePalma as the Apprentice of Suspense. As we will see, even at this inchoate stage he is blending his own ideas with the Hitchcock model.

DePalma's later films are famous for their big set pieces like the Prom Night massacre in Carrie, the chase through the subway in Dressed to Kill, or the shootout on the railway station steps in The Untouchables. They are each wonderfully visceral pieces of filmmaking. Limited to a total budget of about a half million dollars, DePalma resorts to stylistic innovation to produce results in Sisters' two signature sequences. The first one is the murder of Philip and its cover-up. The attack itself hits all of the appropriate Psycho notes. The quickly shifting points of view, the multiple fast edits, and the nerve jangling Herrmann score are combined to harrowing effect. But then DePalma employs split screen technique to show us simultaneously the mad dash by Emil and Danielle to clean up the crime scene while on the other half Grace is standing outside of Danielle's apartment building, desperately prodding the detectives to hurry. This adds real dramatic tension as we watch both segments play out in real time. DePalma's final flourish has the escaping Emil swap screens with Grace and the police moments before they reach Danielle's door.

In the second sequence DePalma uses dream imagery to explain key elements of the plot. He wanted to create something that "avoids the scene in Psycho where the psychiatrist sits down and explains everything."1 Grace follows Emil and Danielle to a local sanitarium. Emil, who runs the place, forcibly commits Grace as a new patient and subjects her to hypnosis while under heavy sedation. DePalma reveals important plot points leading up to the film's climax from within Grace's hallucinatory dreams. She will wake up for a few moments, witness Emil having an impromptu therapy session in the same room with the also sedated Danielle, and then as the camera seems to enter through her eye, we see Grace's version of what she has learned. Grace appears as Dominique in all of these dreams. SPOILERS FROM NOW ON! The final dream is the most surreal and the scariest. It depicts a nightmare version of the separation of the twins. We learn that this had to happen after Dominique attacked Danielle with some garden shears after learning that Danielle was pregnant via Emil. In a subterranean operating room Emil tells Danielle, "You have lost our baby". Danielle asks, "Am I going to die?" As Grace / Dominique watch in horror Emil tells her, "You will be fine." A meat cleaver is passed slowly through the hands of several creepy looking sets of twins to Emil who raises it high in the air as Herrmann's soundtrack comes to a frenzied crescendo. As he strikes, Grace bolts upright in the sanitarium exam room in full scream.

As terrific as the dream scenes are, they are undermined by a tortured soliloquy that Emil delivers to a half out of it Danielle that confirms what anyone who has seen Psycho already suspects - that Dominique is dead and only lives as a part of Danielle's damaged personality. Moments later this sets up "Dominique's" murder of Emil. This unnecessary, clunky piece of exposition is no better than the smug shrink in Psycho.

Luckily, DePalma recovers quickly with a denouement that pins the needle on the dark irony scale. As Danielle is led into custody she tells the police that her sister "died last spring". The breakthrough that the heartsick Emil was hoping for may have been triggered by his own death. When the now apologetic police call on Grace to reopen the case they find her recovering in the care of her parents. Back in her old bedroom, with high school pennants and Beatles photos on the walls, she has reverted to being the dependent. As a result of Emil's hypnosis her only response to their questions is to helplessly repeat, "There was no body, because there was no murder!" The film's final tableau shows detective Larch, high atop a telephone pole overlooking a railway station in rural Quebec. His binoculars are trained on the sofa bed Emil had sent away that we now know will never be claimed.

Brian DePalma of course has gone on to a long career. He routinely works with A-List actors and lavish budgets. He has had huge hits and infamous flops. But none of those films are quite like Sisters. Maybe it was the low budget. Maybe it was the first thrill of trying to "do" Horror. Whatever the reason, DePalma brings a loose-limbed, "anything goes" vision to Sisters that remains intriguing almost 40 years after the fact. I highly recommend it.

Richard Rubinstein, The Making of Sisters: An Interview with Director Brian DePalma, Filmmakers Newsletter, September 1973. (back)