Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

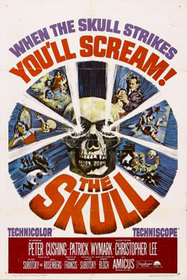

The Skull (1965)

The films of Freddie Francis have always shown the work of a skilled visual craftsman -- one of the very best, in fact -- but also one who performs better when others provide him a creative vision and context from within which he can do his work. I find it rather telling that many of the best films that Francis worked on -- Glory, The Straight Story, The Elephant Man -- were those in which he acted as cinematographer to a visionary director, years after he gave up regularly directing himself. The Skull, made for Amicus in 1965, is a particularly effective case for Francis's talent with a camera and against his knack for creating his own stories. Although the film is hampered by a lackluster script and poor casting choices, its ultimate chance at success rests on Francis's shoulders – for better or for worse.

Dr. Christopher Maitland (Peter Cushing) is a scholar whose particular raison d'être is the collection of artifacts related to evil, both human and otherwise. So, when his supplier, Marco (Patrick Wymark), offers him the skull of the infamous Marquis de Sade, Maitland is fascinated. He becomes even more so when his friend Sir Matthew Philips (Christopher Lee) tells him about the skull's demonic powers. What follows is a night of terror for Maitland as he gains possession of the skull... and the skull gains possession of him.

For the first third, The Skull is chock-full of intrigue as it lays out the story of a man whose interest in the academic nature of evil may lead to evil itself. However, not much after that, a weird entropy sets in – the film begins to hem and haw around every point of interest, as if not sure how to proceed. A glimmer of hope appears when Marco relays a story about the eponymous skull in flashback – perhaps this movie is, in fact, one of Amicus's many anthology films, albeit one with a more-complex-than-usual framing story. However, this proves not to be so; the story continues to dawdle, and it becomes quite clear that the screenplay has a serious pacing problem.

The truth of the matter is that the script for The Skull (adapted from Robert Bloch's short story, “The Skull of Marquis de Sade” by Amicus honcho Milton Subotsky) never feels like it was meant to sustain a feature-length film. Very little actually happens in the course of the film beyond what is described in the synopsis above and all of it seems to take much longer than necessary. Indeed, there are reports that the final version of the screenplay was too short at only 53 pages, and that director Freddie Francis had to improvise additional sequences (including two lengthy silent sections at the middle and end of the film) in order to bring the running time to 83 minutes.1

Additionally, the characters are thinly drawn – an irritation even in the plottiest films. We know little about Maitland as a person beyond his field of study. He has a wife (Jill Bennett) and he appears to care for her, but the marriage seems to exist simply to have a damsel to put in distress when needed later in the film. Other characters, like Sir Matthew, appear merely as sources of exposition, speaking at great length but saying very little.

Only Marco feels like he has any dimension. Although we get a sense of his scumminess early on (his snuff-stained nostrils and the smirking way he talks his way into Maitland's study), we also see, during Marco's conversations with Maitland, that the man really does have an appreciation of the antiques he fences. One sometimes despairs at the dearth of well-rounded characters in horror, so I appreciate it when someone like Marco comes along.

One of The Skull's major problems is almost impossible to consider – Peter Cushing's performance just isn't that good. Believe me, it took me a while to come around to the realization. Every time the man is on the screen, I'm rapt, glued to my seat. However, in this particular case, cinematic charisma just isn't enough. We are never really sold on the character's fascination with evil, a personality trait that is key to the entire plot. When Maitland calls Sir Matthew a coward midway through the film (for not confronting evil head-on), it sounds false, because Cushing's performance – a mix of absent-minded professor and even-mannered gentleman – doesn't suggest a man who would even pretend to be more brave. It's an unfortunate fact, but even when the acting is as engaging as Cushing's, it's still bad acting if it doesn't fit the part.

Likewise, Freddie Francis's direction is enthralling but it never sits quite right. When he's good, he's very very good. His mastery of the visual medium exists on a level above and beyond the mediocrity of the script. Watch the film without sound sometime and you'll see what I mean. The sheer talkiness of some scenes is overcome with deft movements of the camera and ingenious framings. These are moments you may not notice on first view, which is of course the point – Francis unleashes some of his best work when the viewer is otherwise engaged, which allows the audience to keep their attention on the story and not the manner in which its being told.

In particular, there are two suberb examples of fine camera work that come to mind. The first occurs during the auction at the beginning of the movie. The camera is focused on a clearly troubled Sir Matthew when it swings around so that his profile consumes half of the frame, while Maitland comes into view in the background, taking a drink of water. In a moment, Francis establishes the relationship of the two characters, at least in the context of the auction – Sir Matthew will dominate to an unnecessary extreme, while Maitland will casually compete but ultimately he will take the backseat to his colleague. The second example takes place just after the half-hour mark, during a snooker game between Maitland and Sir Matthew. The two men, on opposite sides of the table, are discussing the skull. The shot starts with Maitland, who says his line and then takes his shot. The camera then follows the ball across the table and, with fluid motion, settles on Sir Matthew, who responds. Here Francis uses the mobility of his shot to keep the flow of the conversation going without resorting to a cut, which might have been jarring at that point in the scene.

However, in the film's two major near-wordless sequences -- the dream sequence at roughly forty minutes in and then Maitland's struggle with the skull's influence at the film's climax – we see where Francis, while still doing great visual work, is perhaps not up to the more creative challenges of being in the director's chair. Francis certainly demonstrates boldness in allowing these sequences to run for six and twelve minutes, respectively, without a word of dialogue. He seems to be asserting that dialogue is not necessary to invoke horror. Indeed, both sections are filled with striking imagery: the laughing judge and shrinking, smoky hallway in the dream and the skull's eye view and unnatural lighting in the climax. Watched outside of the context of The Skull, they are both unnerving mood pieces, steeped in atmosphere.

However, neither sequence sustains from a dramatic standpoint when considering the film as a whole. The dream, which is meant to demonstrate the beginning of the skull's hold over Maitland, does no such thing. While the scene is certainly filled with nightmarish imagery and concepts -- trial without charge, domination by perplexing authority, and claustrophobia -- none of them actually relate to what we know about Maitland or the skull. The sequence just pulls standards from the Dream Imagery Songbook, with no real understanding of the subconscious underpinnings of each particular image. It makes no sense, goes on too long without telling us anything useful, and appears to exist merely to pad the film.

The climax does maintain a more coherent relationship to the story; its folly, instead, is tedium. At first, the sheer eeriness of Francis's images and lighting schema is enough to drive this silent battle of wills between Maitland and the skull. Eventually, though, the sequence becomes rather monotonous -- Francis never ups the ante visually or dramatically. The skull holds sway over Maitland until it inevitably doesn't, at which point the skull exacts its revenge. It's a fairly standard, well-worn ending that Francis doesn't really enliven. Sure the visuals remains top-notch, but they never really excel above and beyond what we have already witnessed. Francis's bag of tricks runs out, and he has no new solutions to maintain our interest.

Recommending The Skull is difficult. Clearly the film lacks a proper script, and I wouldn't blame any Peter Cushing fan for wanting to avoid one of his poorer performances. However, it is probably the most visually dynamic film in Freddie Francis's directorial oeuvre, even when those visuals can't sustain the flimsy story. What The Skull does best is provide a peek at the full potential of a highly talented individual. If that is something that captures your interest, this skull's for you.

1 Lucas, Tim. "DVD Spotlight: The Skull." Video Watchdog #142. Aug 2008. Page 39.