Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

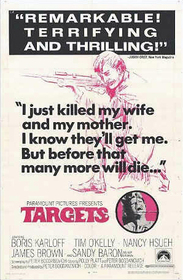

Targets (1968)

One of Hollywood's most endearing strengths is its ability to survive its own cannibalistic impulses. While film is certainly not the first medium to successfully criticize itself, Hollywood's cadre of horror filmmakers have been particularly effective in using self-deprecation and self-parody to pave new artistic paths. Although Peter Bogdanovich is no monolith in the horror genre, as an actor, director, critic, film editor, screenwriter, film historian, author, and general cinephile, his shadow transcends the horror clique. Like all good auteurs, Bogdanovich doesn't restrict himself to one genre; his one great foray into horror, Targets, released in 1968, reveals an acute sense of the genre's history and future. More importantly, he is keenly aware of the relationship between the two. If Targets achieves anything, it reveals the symbiotic relationship between the Old and New visions of Hollywood, particularly as this relationship manifests itself within the horror genre.

Targets consists of parallel plots that intersect at the film's conclusion. One story begins with a film screening. Bogdanovich plays director Sammy Michaels, who has just completed a film starring horror icon Byron Orlok, played by an aging Boris Karloff. The footage we see is from Roger Corman's The Terror (1963). Orlok is disappointed with the film and storms out of the room announcing his unofficial retirement. Michaels pleads with him, and eventually, after much convincing by Michaels and his girlfriend, who is also Orlok's secretary, Orlok decides to make one last public appearance at a local drive-in.

The second story features Bobby Thompson, a low-key Everyman who enjoys shooting rifles and has an attractive girlfriend who wants to marry. Thompson, whose character was directly based on Charles Whitman, the sniper who killed several people from a tower located on the University of Texas at Austin campus, casually proceeds to shoot his girlfriend and her family. Then, without any explanation, he begins to assassinate people from atop an oil tower alongside a California freeway. He moves his sniper practice to the drive-in where Karloff is appearing, and the film's conclusion engulfs the location into utter chaos.

Karloff is clearly playing himself here, and he does so with authentic grace. Orlok wants out of Hollywood, but he knows he cannot easily pull the plug from his popularity. Orlok at one point snarls at Sammy for being an "errand boy" and says, "if you cared about the people, you'd stop making films," yet as the film unfolds, Orlok finds his own advice difficult to follow. Orlok is an obvious reference to the vampire in Nosferatu, which is arguably the archetypal cinematic vampire. Like the vampire in that timeless Murnau classic, Orlok the movie actor also feeds off others. In this case, it's his audience's admiration. Orlok says he is an "antique" and an "anachronism" and reminds Michaels that the "world belongs to the young", yet Michaels the character and Bogdanovich the director fully recognize the importance of tradition. In a sense, all of Hollywood is a vampire; new artists feed off the old, who have also fed off their predecessors. Michaels states, "Without you (Orlok), there is no film." One could easily say the same of Karloff and his many horror films. Thus, Bogdanovich, speaking on behalf of many Hollywood insiders, readily admits that a certain degree of "vampirism" is necessary, even if such symbiotic relationships force awkward personal sacrifices.

Orlok's inability to shake his old persona resonates throughout the film. At one point, Michaels wakes up in bed with him, a perfect metaphor representing the need for New Hollywood to "sleep with" Old Hollywood, and says he was experiencing a nightmare. Not coincidentally, it is immediately after this bedroom tryst that Orlok decides to continue the public appearance. He cannot keep away from those who make films. Orlok also rises to answer the door and his reflection in the mirror scares even himself. At another point, Orlok watches one of his older films and relishes his performance. Old legends don't die easily, even though they know death is inescapable. Orlok's narration to his radio interviewers of the legend "Appointment in Samarra" is also telling in that he now realizes that despite his personal distaste for being a Hollywood icon, he does have an audience and owes them something. Even if his appearance is self-serving, he knows others will benefit. He cannot escape Death, but he can certainly make her wait.

Interestingly, although the early scenes in Targets criticize the backdoor handshaking that symbolized much of the classic Hollywood studio system, the film was essentially produced as a result of such gestures. Bogdanovich's early work with Corman impressed the latter, so he "gave" the young director about 20 minutes of footage that Karloff owed him along with another 20 minutes of footage from The Terror. Bogdanovich couldn't resist the opportunity to direct. Samuel Fuller, one of Bogdanovich's early mentors, also helped by essentially rewriting the original script. Fuller declined the opportunity for credits, and Bogdanovich has been forever indebted.

The film also sparkles in its depiction of Old vs. New Hollywood. After footage from The Terror, which ironically features another rising young icon in Jack Nicholson, Targets begins immediately with a close-up of a dissatisfied movie icon: Orlok/Karloff. The film ends with an aerial shot of an empty drive-in, a location that in many ways encapsulates the highs and lows of decades of film industry trends. For many, drive-ins generally symbolize the death of the high-profile celebrity and the studio system and the rise and popularity of lower-budget B-movies. Specifically, many of these B-movies featured horror films, and this transition from the Karloff driven studio system monster to the B-movie drive-in "creature-feature" marks the evolution of Hollywood as seen through the eyes of a horror fan. It is no coincidence that one of Thompson's first victims at the drive-in is the film operator.

And if Orlok/Karloff represents old "horror", Thompson clearly represents the new. Orlok represents personal terror, a brand of horror where monsters knew their victims and often killed with their hands. Thompson kills in the most impersonal of manners: from a distance with a rifle. He also knows nothing about his victims. The old monsters often had reasons for killing their victims. Revenge, poetic justice, and personal survival were all at the forefront of their murderous vamps. But with Thompson, we really have no clue why he is committing murder. His shots are random, his motivations empty, and his justifications are at best masturbatory. He kills because it makes him feel good, a phenomenon that ushers the visual and narrative appeal of killing for killing's sake into the latter half of the 20th Century. Murder has now become a kind of psychological candy and visual spectacle. Moreover, the classic monsters killed in more isolated instances. For the most part, a murder here or a murder there was their trademark. But Thompson is arguably one of the first cinematic WMDs. His potential for causing mass destruction is evident immediately when he starts pecking off cars on the freeway. Although one never happens, a massive 20-car pile up emerges, more effectively, in the viewer's imagination. Finally, those classical monsters represented The Other. A vampire, werewolf, or mummy clearly is not the friend next door. But Thompson is one of us, an Everyman we see every day in the post office, local diner, and gas station.

Yet Thompson and Orlok have their parallels. Their "falls" both begin from great heights: Thompson from the oil tower and Orlok from the crumbling castle in The Terror. Both also reject their families. Orlok abandons the Hollywood insiders who helped him become famous, particularly Sammy, who Orlok sees as a son and protégé. Thompson completely rejects everything about middle-class suburban life. The assassination of his future in-laws is a morbid reminder of nihilism gone insane. And finally, both strangely end up in the same place: a movie drive-in seeking fame and glory. Although Thompson's last grasp at meaning ends in flames, Orlok's is heroic. He seizes his one last chance at glory by slapping Thompson in the face. Leading up to this slap, Bogdanovich does a wonderful job of blending the on-screen persona of Orlok and Karloff with his off-stage persona. The menacing figure that approaches Thompson could easily be Karloff, Frankenstein, or The Mummy; instead, it is Orlok. What is interesting is that he does nothing monstrous to Thompson; he simply slaps him, perhaps the most human and paternal of admonitions. Not so fast, Karloff the icon seems to be saying. Old legends don't disappear that easily.

Targets is an absolute must that will appeal to many horror fans. As Nate Yapp, Classic-Horror's managing editor once wrote, it is "one of the three 1968 horror films that officially spun the genre into the modern era (along with Night of the Living Dead and Rosemary's Baby)". The genre has been spinning ever since.

Correction: Bobby Thompson

Correction: Bobby Thompson murders his own parents as well as his wife, craftily waiting until after his intimidating father has left for work. No explanation is offered as to why he and his wife are living at the home of his parents. My opinion is that Bobby's murder spree is a kind of retaliation against his father, even charging his purchase of ammunition on his father's credit card -"gonna shoot some pigs!".