Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

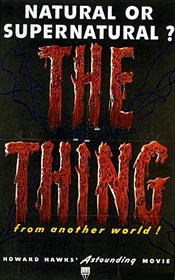

The Thing From Another World (1951)

The Thing from Another World, appropriately abridged and known more commonly as The Thing, is one of the seminal 1950s creature feature films that paved the bridge between the horror and science fiction genres. Filmed in Montana's Glacier National Park and an ice storage plant in Los Angeles, The Thing launched the 1950s onslaught of alien invader science fiction classics including War of the Worlds and the cultish Invaders from Mars. The Thing also established the chilling, claustrophobic tone for later sci-fi horror classics such as Alien, and of course, John Carpenter's faithful remake, The Thing.

Christian Nyby and Hollywood icon Howard Hawks co-directed the film; however, some have disputed Hawks's contributions. Nevertheless, most agree that Hawks was the film's primary creative force. By 1951, his reputation for directorial dexterity was solidified in Hollywood annals with classics such The Big Sleep, His Girl Friday, Bringing Up Baby, and Red River, and many could easily detect the auteur's brands: sharp dialogue, brisk pacing, relaxed performances from all characters, and an astute understanding of a genre's conventions. The Thing has all of these elements.

Nyby's directorial credit was also an extension of Hawks's generosity. Apparently Nyby, who previously served under the dynamic Hawks as editor, needed some directing credits to satisfy his union obligations. Hawks obliged by allowing him to direct portions of the film, but some have suggested Nyby directed only a few scenes and barely warranted such a credit.

Hawks's stature in Hollywood hovers over The Thing like a noir shadow. He used his clout to solicit assistance and expertise from the U.S. Air Force, but officials refused to help because such assistance would sacrifice their public denial of UFOs and alien life. After all, this was the early 1950s, a period in American history replete with Communist fears, space travel, and reported UFO sightings, all of which blended for some creepy realizations among the American public. Ben Hecht and Hawks co-wrote the screenplay, and some critics argue the legendary wordsmith William Faulkner, a long-time buddy of Hawks, may also have assisted. Rumors that Orson Welles contributed to the script have generally been dismissed.

The film has historically been linked with two other genre classics. Also released in 1951, The Day the Earth Stood Still is considered the liberal version of a utopian dream, a world where peaceful ideals and social harmony are touted as supreme answers to a world growing increasingly more dangerous and chaotic. The 1951 Nyby-Hawks classic is considered this film's counterpoint: it is the conservative version, where military officials and scientists grapple over the nation's destiny and ultimately restore peace with force and aggression. Each film serves as a wonderful parallel to the other.

The second inevitable linkage is with Carpenter's 1982 classic. Both share a number of similarities, yet each clearly reflects a unique vision. Both are based on the John Campbell short story titled "Who Goes There?". Carpenter worked hard to remain faithful to that plot. But while Hawks used more science and comedy in his film, Carpenter painted his canvas with a bleaker brush designed to scare the hell out of his audience. The "things" in each film are also notably different beasts. Prior to his 1982 remake, Carpenter paid the original another tribute by including it in the final climactic scenes of Halloween. The kids Jamie Lee Curtis is babysitting are watching this classic on Halloween night. If anything, the films' differences offer fans an excellent opportunity to examine what scared people during two very different historical periods in America cinema.

The plot is relatively simple: Assigned to an Artic outpost, a group of researchers and military personnel along with one journalist stumble upon a frozen spacecraft. As they investigate the strange object set in ice, they find the pilot and bring him back to their station. Unfortunately, the pilot thaws, and they learn that he is a bloodthirsty monster composed of a strange plant-like material. The researchers want to preserve and study him, while the military personnel want to annihilate him. The journalist, naturally, wants to report the news. These competing interest groups wrestle to determine the beast's fate, until finally, the military personnel win.

James Arness, who played Marshall Matt Dillon of "Gunsmoke" fame, is the monster, but he frowned upon this role because his character was too ridiculous. Arness even suggested that he resembled a carrot more than a monster, and at one point, Dr. Carrington, the lead researcher, compares it/him to a carrot. Arness' monster is rarely seen except at the end, and this decision is wise due to the monster's cheezy appearance. Part Frankenstein, part carrot, part Mummy, this beast struggles for an identity. Sometimes, restricting the audience's view of a monster adds drama and suspense; sometimes, this decision is completely pragmatic. With modest budgets and inexperience in a fledgling sci-fi horror genre, some aliens are too absurd for even the camera's eye.

But what makes this film fascinating is the tug-of-war that unfolds between the military personnel and researchers. Many classic films have capitalized on this theme: an outsider or The Other forces friends, families, and communities to bicker and fight among themselves. However, during a time when the "post-industrial military complex" was fully flexing its muscles, tensions between the two main parties in that "complex" are hard to believe, at least to a modern eye. Currently, the incestuous relationship between the industrial and military sectors seems far too diplomatic. But what the public often forgets are the inevitable political machinations that emerge behind the scenes. The Thing offers viewers an intriguing glimpse into that world.

And what becomes powerful yet alarming is the film's portrayal of the military. The men who represent the armed forces are unsympathetic and brutal and thoroughly dismiss any thoughts of conducting research on a murdering beast. They squash the idealistic virtues of Carrington and his band of researchers like a bug. And what seems so alarming is they are right. In the context of The Thing, given the characters' remote location, limited communication tools, and the general paranoia that The Thing fosters, combined with what is clearly its murderous intent, the militaristic option seems far too appealing. Their decision to destroy the beast seems like the only option when compared to Carrington's ambitions. However, in the context of 1950s America, this approach seems incompatible given the easy access to nuclear arsenals the world's two superpowers had. To give too much power to the military, and to run amok in a jingoism that seems on the surface all too plausible, is to commit national suicide. But that illogic seems far too logical in The Thing.

Not coincidentally, the female characters, most notably Mrs. Chapman, serve as a check and balance to this belligerent chauvinism. While she ultimately sides with Captain Hendry, who leads the military faction against the beast, her character at least offers him some comic relief and us the opportunity to see his softer, more humane side. And let's not forget, they are in love. Their romantic bantering is almost comical when juxtaposed against the serious barbs tossed between Hendry and Carrington. Nevertheless, Chapman does at least make Hendry think twice about his plans.

And the romance that develops between the two is classic Hawks. Combined with the reporter's periodical jokes about the news media, Hendry and Chapman's evolving affair is punctuated by many funny lines. Their conversations are often marked by the sharp-tongued, battle of the sexes exchanges that highlight so many screwball comedies. These comical dimensions add a lighter touch to the film that accelerates its already crisp pace. They also offer a balance to the more serious lines uttered by Carrington: "There are no enemies in science, only phenomena to be studied" or "Knowledge is more important than life." The dialogue in The Thing far surpasses that of its peers.

Like many horror and science fiction classics, The Thing is not exactly terrifying, but it does open a provocative window into a unique chapter of American history. Carpenter fans also should enjoy this one, and they may even utter a few chuckles.

I watched the movie for the

I watched the movie for the first time tonight, and I was laughing myself silly for most of it!

One glaring mistake I noted was that this movie was set in the North Pole, where night lasts for the entire winter and daylight the entire summer.

Unfortunately, somebody forgot to tell the movie makers, who filmed day and night sequences! My, the months just fly by when you’re being monstered by a giant carrot!

I also enjoyed the part where one of the actors said of the popsical-alien "Some creatures here on earth come back to life after they die." Zombies and vampires, presumably! He may have meant "some creatures, after being frozen, go into a type of hibernation, but revive after being thawed". But I was laughing too hard to translate it that far until after the credits rolled.

It was a hoot of a picture, but I don’t think it was supposed to be funny when it was made. Still, gave me a good laugh!

Alison

Your review is laughable,

Your review is laughable, grow up.

When have ever been there? I

When have ever been there? I have been several times. For the most part they have both day & night, There are periods of extended days ("Land of the midnight sun") and nights @ times. Start reading something other than comic books and bathroom walls.

Chris, unfortunately you have

Chris, unfortunately you have got your characters mixed up. Captain Hendry is pursuing a relationship with secretary Nicki Nickleson and not Mrs. Chapman, whose husband is the rival of Dr. Carrington. I therefore question most of your other comments.

Having watched this movie sixty to seventy times, since first seeing it on 1950's television, there is little merit to your criticisms of the military as brutal and unsympathetic. The reason that Captain Hendry wants the beast under control is that it killed 2 members of the scientific team Dr. Carrington has left to possibly meet with it. It slits their throats to drain their blood for its own nourishment. He tells Carrington he can do what he wants with the monster as long as it is safely locked up.

In addition, military jingoism in a 1951 science fiction movie is a laughable stretch. You completely disreguard Dr. Carrington's wild sweeping conclusions that this beast is "our superior" in every way, because it has a vegetable rather than animal heritage. It is therefore devoid of emotions and sexual drives.

This movie is a Howard Hawks classic. He took no directing credit because in those days science fiction was a struggling new genre. it had a poor reputation. No director going to lower himself directing this stuff. The monster stays in the background not because of a "cheesy costume", but to give the movie added tension. The location is an isolated Arctic outpost. Adding in a ferocious winter storm and a communications blackout, it leaves them on their own. Hawks creates tension without blood and gore, not an easy task!

The Thing fron another World is truely a terrifing movie. It does it without the Carpenter's version of wall to wall special efffects and gore. Howard Hawks did it with acting and dialogue, something lacking from today's movies.