Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

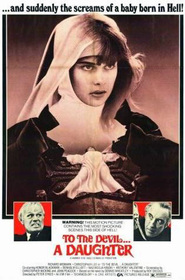

To the Devil a Daughter (1976)

Good versus evil has been a standard cinematic theme, particularly within the horror genre, since the invention of the Cinematographe by Louis Lumiere in 1895. However, as film audiences have become more jaded over the years, the definitions of good and evil have become less clear. Enter To the Devil a Daughter, an ambitious but technically flawed attempt to muddy the line between hero and villain. Produced in 1975 by Britain’s Hammer Films, in cooperation with Germany’s Terra-Filmkunst, To the Devil a Daughter stars both horror king Christopher Lee and Hollywood legend Richard Widmark (purportedly imported for international box office appeal). Supported by a cast of acting veterens and a talented young director named Peter Sykes, To the Devil a Daughter works... almost.

Occult novelist John Verney (Widmark) is on a book-signing tour in London when he’s approached by friend Henry Beddows (Elliott), who asks him to look after Henry’s daughter Catherine (Kinski). Catherine, raised (almost since birth) in a remote convent in Bavaria, has been under the careful tutelage of the mysterious Father Michael Rayner (Lee). As events unfold, Rayner is revealed to be an excommunicated priest heading a cult of satanic worshipers following the demon Astaroth. This cult, with Verney's unintentional help, plans to use Catherine’s body to unleash an avatar of Astaroth onto the Earth.

To the Devil a Daughter is intriguing in that none of its characters are bastions of morality. Verney, himself exhibits questionable morals that make him nearly a secondary monster. He is portrayed as a man so obsessed with finding another story to write and making some money that he’s willing to put his friends in danger. In fact, his decisions often help lead to their deaths. Verney already knows that Rayner and his group are more than the group of "pathetic freaks who get their kicks dancing around in freezing church yards" he’s written about in the past. And yet, he still agrees to have Anne and David help him babysit Catherine, knowing that anyone connected with him will also be a target for Rayner. When Verney finds Anne murdered, his reaction reveals a decided lack of emotion. His short response of “Oh my God... I’m so sorry, David” is cold and distant, demonstrating neither regret or remorse. He's focused only on stopping Reyner, and, by doing so, earning his next big paycheck. It’s only when Verney realizes what will ultimately happen to Catherine, an innocent, that some kind of morality seems to surface. When it comes to Anne, David and even himself, Verney seems to adhere to a form of selective caring, one which demonstrates a blatant disregard for the lives of “flawed” individuals.

In contrast, Father Rayner and his followers are not so much the villains as people seeking to halt the decadence of mankind through devotion to their god. The cultists exhibit a strong sense of order, discipline and focus. One member even endures a torture-filled “birth” ( allowing herself to be killed in the process), just to help fulfill the goal of the group. Such single-minded selflessness betrays a certain kind of value to their actions, a higher purpose that is absent from the “hero's” motives. Wishing only to have one entity, or governing body, overseeing all humankind, there goals demonstrate a certain simplicity which would ultimately result in an end to wars and violence between human factions. Their only error is not realizing the folly of stopping all the smaller wars and disorder by starting the ultimate conflict. They want to help mankind in their own way but they follow the wrong path to do it. In the end, Rayner and his followers are simply misguided, not malevolent monsters we have come to expect.

The direction of Peter Sykes (Demons of the Mind, 1972), combines a tight pace with interesting visuals. Of particular note is his use of the fish-eyed lens (a means of distorting the edges of the frame) in many sequences, using it's unique camera distortion to thrilling effect. The viewer is being given a front row seat to the war going on for Catherine’s soul - with her psyche serving as the battleground. In one scene early in the film, Catherine is escaping from Verney’s apartment. As she is running, she seems to be fighting a battle in her own mind. Fish-eyed visuals of her immediate surroundings, mixed in with scenes of Rayner, make it seem as if he’s attacking her, despite his physical absence. Later, Sykes utilizes similar fish-eyed shots in a dream sequence involving the bizarre impregnation of Catherine. This is the equivalent of mental rape by Rayner, tearing away at Catherine’s perceptions of innocence and virtue. Combined with additional shots of the group engaging in bits of kinky sex acts, the scene works to draw the viewer in by tapping into our voyeuristic instincts, gaudily displaying the re-shaping of Catherine’s mind by Rayner.

Sykes also has a knack for the chase and special effects scenes. He uses editing, music, and stark visuals to liven up an early foot chase between Verney and Catherine. It' s hard to get excited about one person running after another, but Sykes pulls it off by filming the scene so that Catherine appears to be pulled away from Verney by Rayner. He puts physical obstacles in Verney’s way and intercuts the fish-eyed shots of Rayner emanating from Catherine’s mind, so that she appears to be pulled not just physically, but spiritually as well. Later in the film, Sykes nearly tears the roof off with a powerful scene of Verney and David searching the church for an important medallion. During this scene, David is killed in a fiery burst of flame, an often dull horror film trope. Here, however, Sykes twists this familiar trick by focusing on David’s facial reactions, his helplessness mingling with his cries of agony as the flames move along his arms and envelope him. It's a nice mix of stark effect and tragic human reaction. Both scenes are underscored by the excellent use of music, composed by british tv/film veteran Paul Glass. The foot chase features a more pensive, surreal piece suggesting both the determination of Verney and Catherine’s dream-like state, while a more boisterous, chaotic number is used to good effect for the church sequence.

However, To the Devil a Daughter's biggest plus is the decision by producer Roy Skeggs and director Sykes to film extensively on locations in London and Bavaria. Sykes appears to be using the camera lens to show the subtle contrast between a civilized, modern society singed by decadence and chaos, London, and the equally corrupt but more ordered old world setting in Bavaria. Sykes deliberately suggests that these two worlds have more in common than we would think. For example, both the introduction of Verney and his meeting with Beddows take place in one scene at an art gallery/bookstore in downtown London. This is a common place for the selling of wares and everyone there is looking to gain something. Henry Beddows arrives to ask Verney to help save his daughter’s soul. Verney agrees only because he can make a buck. In comparison, the scenes in Bavaria at Rayner’s church show an old style elegance and simplicity, which reflects the stripped down, stream-lined focus of the cultists Utopian views. Sykes uses these visuals to link the idea that money, and the pursuit of it, can invite sin and erode the soul just as much as the singular pursuit of perfection and stability. However the best use of locations, cinematically, is saved for the finale. The entire confrontation between Verney and Rayner is filmed at the Dashwood Mausoleum at St. Lawrence’s Church in West Wycombe, Buckinghamshire. The mausoleum structure is a combination of flint and stone, an old, historic structure that could never be accurately re-produced on a studio set. In this case, the use of such an ornate edifice provides a palpable air of dread and menace to the final battle.

Richard Widmark does a solid job as Verney, investing our dubious hero with a tired, cynical air. Widmark has a distinctive, slightly raspy voice, that, when mixed with the experience he carries from a career playing weary tough guys, helps make Verney something of an anti-hero. In fact, Verney is a throwback to the days of the noir-ish heroes of the 1940’s. Using practiced breathing exercises, as well as a perfected dramatic pause, Widmark embodies the put-upon protagonist – the guy who saw too much, did too much, and was broken down by life before finally being allowed one last hurrah as the good guy. Wikmark's cynic shines during one particular scene, when Verney first confronts Rayner during a phone call. He seems to play with Rayner, pretending he does not know anything about what Reyner is talking about. When a visibly frustrated Rayner baits Verney by verbally identifying him, Verney responds with "And I know you… Michael Rayner. Oh, oh excuse me... FATHER Michael Rayner." Widmark's Verney is too wearied by life to care about the threat posted by Rayner, instead throwing it back in his face.

Christopher Lee matches Widmark with a great performance that mixes passion, determination, and super-ego nicely. Lee has made a career of playing both good and bad guys to equal effect, enabling the horror legend to bring Rayner to life with a mixture of physical movement, facial reaction, and a very theatrical voice. He infuses Rayner with equal parts nobility, fanaticism, and righteousness. Like other characters he has played over the years, including Count Dracula, Lee also allows more than a bit of arrogance to show through in Rayner's character. Further, Lee is expert at conveying emotion through a simple look or stare. Case in point is the scene involving the aforementioned demonic birth. On the surface, it is a revolting mix of blood and torture; however, it is intercut with shots of Rayner, wide-eyed and smiling gleefully. In his mind, a very beautiful event is taking place, his mission going completely as planned, and his satisfaction is reflected by his carefree countenance.

Acting and direction aside, To the Devil a Daughter does have some excruciatingly frustrating problems that detract from an otherwise enjoyable film. The presence of three scriptwriters is usually a sure sign of dialogue and story trouble. These writing problems are particularly evident in the lack of back story and lame dialogue. Lines such as “It is not heresy and I will not recant!” are almost embarrassing, and undermine the seriousness and credibility of the story. This is compounded by the lack of exposition. Other than money, we have no hint of Verney's motivations, and there is no explanation as to why Beddows suddenly joined the cult and then signed Catherine over to them. If the characters were more fleshed out, the the viewer might actually become emotionally involved with them. As it is, because of the lack of backstory, To the Devil a Daughter fails to be emotionally engaging. As a result, many of the more shocking scenes fall strangely flat, since, as an audience, we just can't be bothered to care.

Just when you think this film has enough problems, the producers hit the viewer with a cinematic cardinal sin, scrapping the original (and, reportedly, much better) ending in favor of an extremely dull and abrupt one. The original ending had Verney throwing a stone, soaked with blood from a disciple, at Rayner, hitting him squarely on the left temple. Rayner collapses but does not die.. Instead, he gets up and tries to go after Verney and Catherine, only to be struck down again by a lightning bolt and killed. Instead of an exciting, elaborate finale, we get a yawner that hinges on a wild, improbable stroke of luck as Reyner dies when the stone hits him in the head. As an audience, we really deserve more credit than this.

Any film that tries to be different or exhibit a fresh approach should be applauded, even if it is flawed. Striving to be a twisted take on good and evil, To the Devil a Daughter is more a film about wanting and having. It wants to be a classic turn on morality but ultimately settles for being a decent piece of late-night horror fare to entertain the fans. Still, if you’re looking for a genre film that, in spite of its problems, strives to be more, this one makes for worthy viewing.