Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

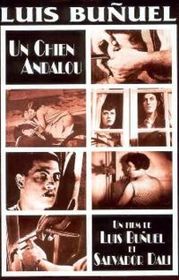

Un Chien Andalou (1929)

Since its release in 1929, Un Chien Andalou has remained one the best and most famous examples of surrealist cinema. It does exactly what surrealist works are supposed to do: sequence random images and events so as to touch its audience in a way that logic cannot. Though it is not a horror film per se, in which the viewer is threatened by a monster, a madman, or some other tangible force, the film does contain a number of horrific images, and its dreamlike construction can at times instill a fear beyond rationality. Director Luis Buñuel and artist Salvador Dalí compile images and scenes that will make you cringe, laugh, vomit, and cock your head - and they compact them into seventeen unforgettable, never-boring minutes that constantly seem to draw from the most hidden depths of our unconscious. Put succinctly, Un Chien Andalou is a masterpiece.

The film begins with what is still one of the most surprising scenes of cinema. A man sharpens a razor, looks at the moon, and places it up to the eye of an apparently compliant woman. The camera cuts away to a thin cloud passing over the moon. It then cuts back to a close-up of the woman’s eye being sliced open (a scene that, Jamie Russell points out, probably influenced Italian horror master Lucio Fulci’s penchant for eye gore). It is difficult to tell whether the cloud passing over the moon is meant to serve as an inspiration for this optometric barber or to suggest that we’re going to be shown only a symbol of the event, forcing down our guard before we’re assaulted with the painful image. Such is the way of Un Chien Andalou: never really making sense, but always offering just the merest hint of logic. This, of course, makes it even more bewildering.

If you can make it past this first short scene, you should be okay for the rest of the film. It becomes no less strange, but it lets up significantly, though not entirely, on the gore. Because of the film’s lack of continuity and short length, to summarize it would be to give everything away. Instead, I will highlight some of its chief components. Un Chien Andalou is a sequence of grotesque and random events put together as if they somehow make perfect sense. Along with the opening scene, some of the film’s more famous images include a man staring interestedly at his hand as ants crawl out of it, and a woman dressed in a man’s suit, prodding a severed hand in the middle of the street. If you’re wondering what the contexts of these scenes are, you’re missing the point. There is no context. The aim of this film is not to tell a story, nor is it to purposely conceal some social message. Its aim is to find images from deep within and bring them to light so that we can better understand ourselves. For the surrealist, this understanding is made possible when the nonsensical is found just as deserving and valuable as the sensible. It is the other half of life, and it, too, needs to breathe.

There is one part of this film that I always find to be exemplary of its overall method. After a woman walks over to watch the hand-hole-ants along with the man to whom the hand belongs, the film steps aside from what very loose narrative there is and fades from the ant hole to a visually similar shot of underarm hair (which, it is later revealed, belongs to the same woman). After a second or two, the camera fades to another visually similar shot of what appears to be some sort of urchin or spiky bush. In any other film, this would be a moment of epiphany (So that’s what it means!), made possible by a camera benevolently cluing us in to the bigger picture. In this film, however, there is no connection. These objects are being shown to us for no other reason than ants look like underarm hair looks like urchin/bush object. Like the image of the cloud passing over the moon, it is difficult, and perhaps impossible, to say whether Buñuel is actually trying to trick us into thinking there’s an intended meaning to the images (supposedly, he was a pretty mischievous guy), or if he’s doing it with the expectation that we’ll understand that there is no logic to it. Either way, the images, like every other aspect of the film, have no intended meaning. Paradoxically, this lack of intended meaning is what gives Un Chien Andalou it’s real, true meaning.

In fact, let’s talk about “meaning” for a moment. Some people, including Buñuel’s son Juan Luis, claim that Un Chien Andalou (and presumably all other surrealist art) can never be analyzed or understood. This is not entirely accurate, however. If it were, we would have to kiss psychoanalysis bye-bye, which is the very place from which surrealism came. It is true that you will get nowhere if you proceed by applying logical thought to this film, but if you feel your way through it, there is often something to be found. That’s the whole point of surrealism. It is based on the idea that if we allow seemingly random images to surface from the unconscious, we can discover deeper truths about ourselves than we could if we consciously set out to create a certain work of art. Buñuel’s son may disagree, but I trust the truthfulness of subconscious material much more than the ideas I have organized myself. It was Breton, the father of surrealism himself, who said, “Can’t the dream also be used in solving the fundamental questions of life?” I think it can, and I think Buñuel would agree.

There are moments in Un Chien Andalou at which we seem to be witnessing a universal truth. Some are sublime, such as a bare-backed woman fading into nonexistence; others are subtly horrifying, like the stone-still figures of a couple half-buried in sand. Usually, the best a film can hope for is to stumble upon one or two such images. Un Chien Andalou devotes its entire runtime to finding them.

This review is part of Miscellaneous Foreign Horror Week, the last of five celebrations of international horror done for our Shocktober 2008 event.

The title, which translates to "An Andalusian Dog," is itself a surrealistic element, as the film has nothing at all to do with either dogs or, as far as I can tell, Andalusia.

Russell, Jamie. Book of the Dead: The Complete History of Zombie Cinema. England: FAB Press, 2006.

"Epilogue: Dalí and Buñuel." Un Chien Andalou. DVD. Transflux Films, 2004.

I saw this short film back in

I saw this short film back in 1975(?) when I attended David Bowie's "Black and White Flourescent Light Show" or probably better known as "The Return of the Thin White Duke." I've been wondering if anyone else had seen this. I still remember the screams of the audience (both male and female) when the eye was sliced open. This was his "opening" act. Gotta love Bowie for his artistic side and his love of surrealism.

I've never seen that, but it