Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

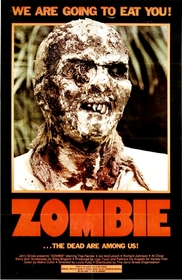

Zombi 2 (1979)

In 1968, George Romero revived the zombie genre with Night of the Living Dead. In 1979, Lucio Fulci brought the genre full-circle by taking it back to its Caribbean voodoo roots in Zombi 2 (aka Zombie1). He also revitalized the horror of the living dead by creating a movie even bleaker than any of Romero’s zombie films. Zombi 2 is a maximally distressing vision of a world flipped on its head.

The plot is just here to serve Fulci’s greater concerns of brutal terror. A woman named Anne Bowles teams up with reporter Peter West to go to an uncharted Caribbean island called Matool, in search of her father. As they search for him, they find themselves surrounded by the walking dead. Then they try to survive. That’s pretty much it.

The Caribbean setting of the film is not only the birthplace of the zombie myth, it is the perfect place for heightening viewer anxiety. By taking the genre back to Caribbean voodoo, Fulci also enacts a second apocalypse — the apocalypse of reason. It is bad enough that the dead are walking, but in non-voodoo zombie films, there is always at least the hope of a logical explanation, such as radiation or a virus. Here, though, radiation and viruses are explicitly ruled out, along with basically everything else. It eventually becomes apparent that voodoo is the one likely source of the problem. The voodoo myth that the western world has comfortably disregarded as impossible superstition becomes an undeniable truth. This subversion of basic reality coupled with zombies is the perfect harrowing experience. The entire world, now, is foreign to us.

Fulci primarily concentrates on creating disturbing visuals. First and foremost are the zombies themselves, which look exactly as zombies would probably really look. Let me go back to Romero again. In his Living Dead films, the zombies are sometimes bloody, wounded, and missing random chunks of flesh, but are otherwise in good condition for corpses. They might be occasionally scary, but let’s face it: Romero’s zombies are fun to watch! Fulci’s zombies, on the other hand, are revolting to the point of nausea. These bodies are significantly decayed (except for those just recently killed, which are almost unidentifiable as zombies), and they rise from death as rotting piles of maggoty flesh. They horrifyingly force upon us reality of what we will all eventually become (minus the walking around and cannibalizing).

The physical violence is equally uncompromising. There are, of course, scenes of zombies eating humans, as is pretty much requisite for the genre, but Fulci takes the gore to the next level. The film’s most famous example of this is the “eye splinter” scene. In one zombie attack, a door is broken, and out sticks a foot-long long, jagged, pointed splinter of wood. In complete graphic detail (well-lit, too), the zombie slowly impales the screaming woman’s eye directly onto it, causing greenish-white goo to ooze out before the white of the eye rips open. There are also grim scenes of a doctor wrapping recently deceased patients in blankets, tying them up, and shooting them in the head so as to prevent or stop their zombification. These scenes are unabashedly straightforward, explicitly portraying all the violence of his morbid duty. Zombi 2 is not only metaphysically horrific; it is viscerally brutal.

Adding invaluably to the film’s bleak outlook is its synthesized score, composed by Fabio Frizzi and Giorgio Cascio. It is, more than anything, mournful. Its slow, constant beat precisely evokes what it must feel like to be pursued by a zombie horde, and its repetitiveness brings out the inescapability of the anguish caused by all that is happening. Whenever a zombie kills someone, the music ceases, shifting the emphasis to the unnerving sound of characters screaming in pain. The score works perfectly with the images; the screen shows us the horror, and the music makes us feel the dismay.

One department in which the film does lack is the character development; the characters seem capable only of discussing the immediate situation and looking frightened when something scary happens. However, I would not say that the film fails in this respect because it doesn’t really try in the first place. The function of the characters is purely to have people to follow through this rise of the dead. This works well because instead of thinking about the characters and how they develop, we are ourselves forced to feel how psychologically devastating it could be for something like this to occur. In a literal sense, of course, we have little to worry about in the way of the dead awakening to devour us (though who really knows?), but figuratively speaking, what happens when we are forced to confront that past which we have buried? What is it like when our accepted truths turn out to be empty? These are inherent themes in any zombie film, and they are portrayed here as bluntly as ever.

This film offers no hope of happy endings, only of survival — and even that is rather limited. When the world turns out to be drastically different from what we previously understood it to be, we can never again trust any universal law. Here, the despair of such a situation is brought perfectly to life. We cannot hope to fix it; all we can do is try to adjust. I imagine that if all the laws of the universe really did flip upside-down, the feeling would not be very different from watching Zombi 2. In short, there’s nothing fun about this movie. It is the very definition of macabre.

This review is part of Lucio Fulci Week, the third of four celebrations of master horror directors done for our Shocktober 2007 event.

- The numerical discrepancy between the titles lies in its original release. In 1978, when Romero’s Dawn of the Dead came out, Italian director Dario Argento released an edited version of it for his own country, with Romero’s permission. The Italian title was Zombi: Dawn of the Dead. When Fulci released his film shortly after Argento’s Zombi, the producer titled it Zombi 2 in an attempt to play off the success of the Romero/Argento film by unofficially passing it off as a sequel to Zombi. Neither Romero nor Argento, however, had any involvement whatsoever in Zombi 2.

The numbering issue gets more complicated with the sequels. There are several films that bear an alternate title of Zombi 3 (including Hanging Woman, a film made five years before Zombi: Dawn of the Dead). An official Zombi 3 was eventually made by Fulci and Bruno Mattei in 1988. There are also multiple Zombi 4s (official Zombi 4 is the 1988 Claudio Fragrasso film Zombie 4: After Death) and Zombi 5s (there is no official Zombi 5, although Shriek Show is currently passing of Claudio Lattanzi's 1987 Killing Birds with that title).

In Great Britain, Zombi 2 is known as Zombie Flesh Eaters and the sequels follow the numbering scheme from there. Zombi 3 is Zombie Flesh Eaters 2 and Zombie 4: After Death is Zombie Flesh Eaters 3.