Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

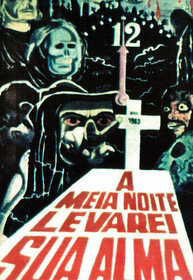

At Midnight I'll Take Your Soul (1964)

Zé do Caixão (or as he's known in the United States, Coffin Joe) is something of a horror film legend and obscure cult figure all at once. The character, the creation of Brazilian actor-writer-director Jose Mojica Marins, is only infrequently included in books on the genre and only one tome (as far as I can tell) has been utterly devoted to him. Yet once you've seen him, you're not likely to forget him; from his all-black suit to his long, curved fingernails, he's an imposing figure. My first Zé do Caixão sighting came in the pages of Phil Hardy's Encyclopedia of Horror, in a publicity still from This Night I'll Possess Your Corpse, which had Zé leering over a female victim, all ten of his fingers hovering like talons over her eyes. I imagined any number of awful things that could happen with this character, and worse things still when I heard the words “hallucinogenic” and “psychotronic” bandied about in the descriptions of his movies. Perhaps eight years of anticipation did me in, but when I finally sat down to the very first Zé do Caixão film, At Midnight I'll Take Your Soul, I found the actual experience a bit disappointing.

At Midnight I'll Take Your Soul has been cited as Brazil's first horror film, and the country's newness to the genre shows -- they definitely get the horror idea, but they're missing a plot. Instead, the film follows Zé do Caixão (Marins) as he commits increasingly despicable acts of violence and blasphemy, all while searching for a woman to bear his child. The more vile Zé can be, the better. Eat meat on Good Friday? Make sure it's cooked. Cut off a couple fingers? The guy was trying to make off with the poker winnings. Kill his wife, then his best friend? They're in the way of his personal propagation. Rape the innocent fiancee of the aforementioned dead friend? He's got babies to make! Essentially, the point of At Midnight is to demonstrate how a single person can maximize their potential as a complete dick.

“Wait a minute,” you might say. “Digits dismembered, compadres killed, and virgins violently violated? That's significantly worse than 'dick' in my book.” I would usually agree, but Zé seems to be a special case. He's never really portrayed as evil, just as ridiculously self-involved. His atheism, mixed with a little of that old Nietzschean will to power, puts him above the craven, superstitious fools in his village – or at least, this is what he believes. The townspeople, in turn, are easily cowed by Zé; they rarely confront him about his behavior and they refuse to stand with those who do. Even when Zé commits brutal violence against another in full view of witnesses, charges are never brought against him for “lack of evidence.” Since he has such utter belief in his own actions, and his environment is one that perpetually fails to enforce society's law against him, most of the heinous acts Zé commits (save the brutal, though largely unseen, rape) can be viewed the same way one would view a bully stealing a lower-classman's lunch money – we decry the aggressor and wish the aggressed would do something to fight back. The overall effect is that much of At Midnight comes off as quaint, because while Zé would like to be a terrifying figure, he simply isn't.

I should qualify that last statement -- to the average American audience, Zé probably isn't a terrifying figure. However, in Brazil, it's a different story. Brazil is a highly Catholic nation (over 90% of the population considered themselves members of the Catholic Church in 19601) and very devout, and At Midnight was made just after Brazil's national censorship board had dissolved. Enter this madman in black, appearing large as life on the movie screen, relishing in his defiance of all the customs and practices that the audience holds sacred. Zé de Caixão was like nothing Brazil had seen before -- a radical element, an atheistic wolf looking hungrily at the religious masses, who suddenly feel very much like sheep. I can imagine many of those audience members had nightmares of a man in black, laughing at them and their God.

Without good presentation, however, Zé is just an overdressed talking head. That's where Jose Mojica Marins, director, comes in to give him a more forceful presence. Although clearly working with limited resources – with the exception of a few outdoor shots, At Midnight was filmed in a studio about 600 square feet in size – Marins makes the best of the situation, creating a number of atmospheric sequences in the very finest tradition of classic horror. The director's best work can be seen in the film's climax. An old witch has told Zé of the numerous harbingers that will precede the fulfillment of the curse in the title. Among these omens are a black cat crossing Zé's path, the sound of footsteps when no-one is following, and the death call of an owl. Zé scoffs, but soon each prediction comes true. Marins carefully builds the tension as the sequence with great use of chiaroscuro lighting and ambient sound. He allows each of the foretold signs the space to manifest themselves fully, so that both the audience and Zé can grasp their fatal significance. And, as Zé's desperation visibly mounts into hysteria, the shadows close in and the sound amps up and the film slips into its hallucinatory final moments, which I won't spoil for you, except to say that they are just as effective as their lead-up.

Marins has carried Zé do Caixão into two direct sequels (1967's This Night I'll Possess Your Corpse and Embodiment of Evil, released just this year), a number of stand-alone features, a short-lived television anthology series, and a comic book. Clearly, he discovered a unique character who would live on for decades after his first appearance. Unfortunately, Zé (at least, Zé as he appears in At Midnight I'll Take Your Soul) seems to be more effective for the people of Brazil, his intended audiences; American viewers might just write him off as weird. Weird, however, is not necessarily bad, and Marins has enough skill behind the camera to warrant at least one viewing of this cult classic.

This review is part of Mexico/South America Week, the first of five celebrations of international horror done for our Shocktober 2008 event.

1 "Brazil Religious Demographic Profile." The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. Tracy Miller, editor. Retrieved 27 September 2008. <http://www.pewforum.org/world-affairs/countries/?CountryID=29>