Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

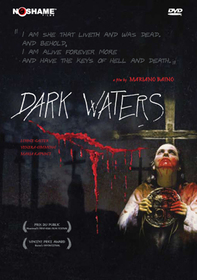

Dark Waters (1993)

That was weird. Those were the first words that spilled out of my mouth as the end credits rolled on Dark Waters, a British/Italian/Russian co-production filmed in post-Soviet Ukraine. Directed and co-written by Mariano Baino, Dark Waters is a singular experience. Steeped in Lovecraftian influence, the film can be dizzying, even maddening, to watch. However, with the captivating direction and surprisingly engaging story, Dark Waters may actually be worth your time. It is not, however, a film for the feeble-minded.

After her father dies, Elizabeth returns to the island of her birth, both to investigate a strange convent her father has been making payments to for years and to visit a friend of hers who is in residence there. Upon arriving, she makes friends with an acolyte named Sarah, and then the weird stuff starts happening. The nuns are killing people, namely Elizabeth’s aforementioned friend, there’s a strange blind oracle-painter in the catacombs, and hints at an ominous demon cult and a Beast in the basement. And Elizabeth, confused and English, is caught in the middle of it.

The first thing anyone would notice about Dark Waters is that for the opening segment, the film lacks a score. There is absolutely no music, or, for that matter, any dialog. That is not to say, however, that the screen is silent. Rather, every sound made seems to echo and resonate, sounding louder than it really is, or at least louder than it should be. And louder than any other sound is the water. Rain is pounding down in torrents outside the convent walls, dripping down in loud, dramatic plunks through cracks in the ceiling and, at the very end of the scene, rushing inside with a roar that rivals thunder. The sound of water, and accompanying noise, builds suspense, provides audience cues, and, at the end, delivers a final shock that no music could accomplish. And, further, by not relying on man-made sounds, this first sequence seems more raw, more real, than the rest of the film.

This clever use of sound is quickly complemented by the brilliant direction. Baino is a master of light and shadow, and the world he creates with them sets the tone for the entire film. The convent, which lacks electric lighting, is dramatically lit with candles. The candles' shadows bounce and flicker, and the walls writhe between light and darkness. This effect is most obvious in the catacombs, the brightest area of the convent. While there are thousands of candles, brilliantly lighting every scene, their shadows also create the darkest crevices, which seem as if they could hide any manner of secrets.

While most pronounced in the well-lit catacombs, Baino's use of the shadow/light contrast is also apparent during dark scenes. Most of the rest of the convent is sparsely illuminated, often by a single candle. There are many shots framed half in shadow, half in light. The effect is eerie, causing nuns to glow unnaturally, or to suddenly emerge from concealing darkness. At times, the light framing was so masterfully done, I almost wondered if I wasn’t watching a Mario Bava film.

The setting, of course, doesn’t hurt when it comes to creating appropriate ambiance. Convents are just creepy, which is a sentiment reaffirmed when Elizabeth admits to Sarah that she used to be afraid of nuns as a child. And well she should be. Stern, unfeeling women clothed from head to foot – what’s not to be scared of. Who knows what they could be hiding under that habit? The women aside, the building is equally unnerving. Ancient and deteriorating, the island convent of Dark Waters had fallen into disrepair. It almost seems to have succumbed to some sort of decaying disease. The walls are crumbling, the tapestries old and torn, and the doors are practically falling off their hinges. The only area that hasn’t fallen victim to the ravages of time are the catacombs, which are well-tended and surprisingly warm for an area that houses only death. The implication, that death thrives while the life around it decays, is hard to miss.

However, decay is not the only theme Dark Waters has to offer; there are also some very strong religious connotations. During the opening sequence, when the water is pouring down, we’re treated to several close-up shots of religious icons, being drizzled in water. In particular, the Christ on the crucifix is pictured several times, with water dripping on his head, obviously hinting at the sacrament of baptism. This theme is compounded near the end of the scene, when the church sanctuary is flooded with rushing water. The baptismal waters, once gently dripping, are now raging. They are murderous and destructive, destroying the sanctuary and nearly drowning the priest who had been at prayer. The metaphor is completed when the priest, struggling to reach the surface, takes a gasping breath only to be impaled on the point of the now broken cross. It is a baptism not into new life, but into death.

It would be easy to say at this point that Dark Waters is also a condemnation of religion, but to do so would be to miss the point. In fact, the Mother Superior gives it all away within Elizabeth’s first hour at the convent: Sometimes there are necessary evils. When Elizabeth’s friend is murdered by a nun, an act we are privy to early in the film, her blood drips onto the crucified Christ, as the water had before, baptizing him in blood. It’s evil, but, in its way, it is also necessary. There are greater evils afoot, and there is more in the balance than the life of a single girl. Dark Waters posits that religion is an evil, which tears people and countries apart, but that it is the lesser of two possibilities. The secret lurking deep in the catacombs is far more terrifying and far more dangerous than religion, and without that security, that necessary evil, we would be at its mercy.

The dark, nearly hopeless, thematic undertones are not surprise when you consider the source material for the story – none other than the illustrious H.P. Lovecraft. Dark Waters is actually loosely based on the novella The Shadow Over Innsmouth, though they had to tone back the monsters because of budgetary constrains. However, when there are monsters, there’s no mistaking their origins. The Beast herself is a mass of gaping mouths and wiggling appendages, and one critical member of the convent, when their true form is revealed, is a half-monster, half-human atrocity (told you they could be hiding anything under those habits). Also, much like the original Lovecraft story, the island and the convent have both fallen into decay, much like H.P.’s New England town, and are practically crumbling under the weight of evil.

However, the real Lovecraftian influence is not in what the story tells, but in how the story is told. The threads of story are revealed as much in flashback, resurfacing memory and strange dreams as they are in the actual events. Elizabeth often finds herself dreaming of strange creatures in the catacombs or a disturbed child who eats raw fish off the beach and eviscerates cats. In fact, as the movie progresses, these dream sequences bleed so completely into reality that it is often hard to make out what is real and what is fantasy. And, in the end, it doesn’t matter. Lovecraft knew that horror is based as much in the psyche as it is in the world, and Baino wisely follows his lead. By the time the Beast is revealed in the final scenes, we don’t know whether this real or dream, and it doesn’t matter any more. We are dizzy and confused by the previous events, it might as well be real. It’s just as terrifying either way.

The story construction makes Dark Waters very hard to follow, but it is readily supplemented by the brilliant direction and complex religious themes. It could easily be said that there is something in Dark Waters for everyone. However, in order to enjoy it, it really needs to be taken as a whole – the dizzying story embraced and experienced. If you’re willing to enter that kind of mindset, that kind of half-fantasy world, Dark Waters has the potential to be understood not only as a creepy religious horror, but as a fine addition to Lovecraftian filmmaking.

This review is part of Miscellaneous Foreign Horror Week, the last of five celebrations of international horror done for our Shocktober 2008 event.