Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

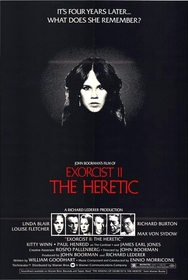

Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977)

Are you one of those growing numbers of horror film fans inflicted with sequel-itis? That is the condition, caused by money-hungry studio execs, that affects the areas of the brain that block impulses to see a movie, no matter the quality level, just because it has a favorite returning character and a number added to the title. If you're looking for a cure, you won't find it with Exorcist II: The Heretic, a good-looking film with a big budget and even bigger name cast that still manages to be a mess on so many levels.

Four years after the death of Father Merrin near the end of The Exorcist, the Vatican dispatches Father Philip Lamont (Richard Burton) to investigate the events surrounding Merrin's demise. His search leads him to New York and Regan MacNeil (Linda Blair, in full coquette mode), the young girl whose demonic possession was the focus of Merrin's exorcism attempt. Still being plagued by strange nightmares Regan has been left, by her mother, to the care of Dr. Gene Tuskin (Louise Fletcher) at her psychiatric facility. Tuskin thinks Regan's dreams hold the key to her recovery, while Lamont thinks Regan knows more than she's letting on about Merrin's death. Aided by a hypnosis machine, Tuskin and Lamont link to Regan's mind in an effort to unlock the mysteries. What the pair ultimately discover is another presence growing inside Regan and that the horror may be beginning again.

John Boorman, himself no stranger to genre work with sci-fi and fantasy entries like Zardoz and Excalibur under his belt, takes his lone stab at the supernatural horror sub-genre and misses the mark completely. His customary flawed, original characters are nowhere to be found. In their place are the usual horror stereotypes: a faith-challenged priest, a disbelieving doctor, the innocent young heroine. The only character missing was the thick-headed but intrepid reporter/cop who gets in the way of things and barely survives or is killed by the finale. Much of the blame for the presence of these cardboard caricatures falls into the relatively inexperienced lap of scriptwriter William Goodhart, a playwright with only three screenplay credits to his resume, Exorcist II being his only horror effort.1

To be fair, Goodhart does resolve some dangling threads from The Exorcist, explaining why the demon Pazuzu has reappeared on Earth, why it targeted Regan originally in the first film, and why it's obsessively pursuing her now. Goodhart expounds on this with an inspiration he received from the belief, coined "The Omega Point" and originated by French philosopher and Jesuit Priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin,2 that man and nature will reach a oneness with God, moving toward a level of cosmic perfection. Lucifer, through Pazuzu, would seek to interrupt this through possession of anyone with acute empathic powers. People like Regan who exhibit these abilities are considered be considered stepping stones to a level of evolution where there would be total goodness and consciousness. It definitely provides a creepiness and underlying meaning to the scenes where Lamont links with Regan's mind when attached to the hypnosis machine and slowly realizes that many of the images he's seeing are actually coming from Pazuzu, not Regan. The demon is once again in possession of Regan, gaining strength to wreak chaos, and she's unaware of it.

Unfortunately, the hacksaw editing job done by Boorman and the post-production crew pretty much renders the narrative incomprehensible. Sometimes good post-production editing can shore up a film with story coherence issues. In fact, Boorman did yank the film after premieres for re-editing after audiences mostly laughed at the film.3 The cutting serves only to exacerbate things by causing the story to ping-pong even more wildly back and forth and back again. The film bounces between the main action, a sub-plot about Lamont's wavering faith, and a story thread dealing with a young African boy possession victim of Pazuzu's (played as an adult by James Earl Jones, in a thankless cameo) with all of the subtlety of a highway car wreck. Several inserted flashback scenes of Merrin dealing with African natives add to the confusion.

The lone bright spots of Exorcist II: The Heretic, are the high production values and the overall look of the film. Dick Smith is called on once again to recreate the hideous face of the possessed Regan for the flashback scenes and re-affirms his mastery of grotesque makeup. Albert J. Whitlock handles the visual effects scenes (the swarming locusts, the destruction of Regan's Georgetown home to name a few) with his customary aplomb. There's even some stunning camerawork by cinematography veteran William A. Fraker (including some panoramic location shots of Glen Canyon, Utah and Page, Arizona, both subbing for Africa). Topping the visuals off nicely are the exteriors shot for the finale, done at the very same house in Georgetown, Washington, DC that was immortalized in The Exorcist.

The final nail in the coffin of this frustrating viewing experience comes, fittingly enough, in the film's final minutes. It is, perhaps, very appropriate that a film that lacks a coherent narrative should have a climax as out-of-control silly as this piece of celluloid has. As Lamont struggles to exorcise Pazuzu from Regan in the upstairs bedroom of her old Georgetown home, the building begins to literally split apart (does homeowner's insurance cover demonic possession?). At the same time, outside the building, Tuskin and her assistant are treated to a car wreck and the doctor is forced to watch the assistant catch fire and die in front of her. I half-expected a dam to burst and a laser light show either from the sky or the cracks in the building. Instead of having an understated, or muted, ending that could have provided the barest stability to the story, we get an Irwin Allen disaster sequence with a spiritual slant.

Watching Exorcist II: The Heretic can best be described as being similar to watching a flower bed completely covered with an abundance of floral varieties in all their eye-popping color and splendor. If you push aside the flora and look more closely at the base, you see and smell lots and lots of manure. Essentially, this also defines what Hollywood film sequels generally are. However its defined, Exorcist II: The Heretic is just one more package of old manure that's been wrapped, given a familiar name and a new number, and re-sold to market.

- IMDb.com

- Deatherage, Will. "Teilhard de Chardin: Man's Future." Suite101.com. Published 04 March 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2010. <suite101.com>

- Chaw, Walter. "Rich Man, Boorman: Film Freak Central Interviews John Boorman." Film Freak Central. Published 13 March 2005. Retrieved 19 May 2010. <filmfreakcentral.com>

Trivia:

Boorman pulled the film out of the theaters twice to re-edit it.

I think it was more of a case

I think it was more of a case of flawed process. They had some intelligent ideas and the making of a good story but completely bungled it. The worse was that song and dance number they forced Regan to perform.

The exteriors for the MacNeil

The exteriors for the MacNeil house weren't shot in Georgetown -- the city refused permission, prompting Boorman to have the house and adjacent stairs built in studio.