Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

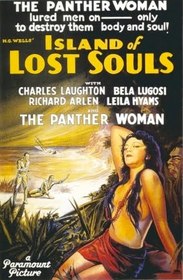

Island of Lost Souls (1932)

With the installation of the Motion Picture Production Code in February 19301 Hollywood, suffering from a damaged image through much of the silents era due to off-screen star scandals and production of some risque films, finally bowed to political pressure2 for increased censorship. Full enforcement of the code, however, would not happen until 1934, when the chief censoring body, the Hays Office, was finally given final editing authority over the studios. Until then, many juicy gems, like Paramount's 1932 horror classic Island of Lost Souls were able to sneak past editor's chopping block with all the delightfully overt and lurid elements intact.

Shipwreck survivor Edward Parker is picked up by another ship, the Apia, which is en route to deliver animal cargo and supplies to a tiny island run by Dr. Moreau. After sending a cable to his fiancee Ruth, who's waiting for him at his original return port, Parker fights with Apia Captain Davies and ends up being tossed overboard. Once on the island, he discovers that the deranged Moreau, aided by disgraced medical doctor Montgomery, has been carrying out gruesome genetic experiments, transforming animals into half-human monstrosities. As Parker desperately tries to escape the island, he develops an attraction to one of Moreau's experiments, a panther woman named Lota. Ruth, meanwhile, joins a rescue ship to go after him. As Ruth arrives and reunites with her fiance, both land in the middle of a nightmarish revolt by Moreau's grotesque victims. A fight for survival ensues as the two struggle to get to safety.

Nimbly mixing tight editing, eerie sound effects, near ballet-like stage-blocking, dim lighting and shadows, Director Erle C. Kenton offers a film that is a clear view through a looking glass into a world of pure wicked sadism. Could this be a progenitor of the torture porn movies so prevalent at today's multiplex? There's Parker's shocking first view of the inside of the House of Pain and the vivisection going on. The blood-curdling scream coupled with the facial closeups on the horrified Parker and the maniacal Moreau make for a raw, unnerving scene. The finale is even more brutally blunt in its depiction of revenge and total bloodlust, with the human-animal hybrids advancing on Moreau en masse as he cracks his whip against them in futility, gleefully carrying him into the House of Pain for one last act of agonizing blood-letting.

The moody, disturbing visuals and varied lighting that permeate this film come from the eye of cinematographer Karl Struss. Struss does an amazing job of taking the conventions of how to use camera and lighting to enhance positive and negative mood, twisting and, in some cases, turning them on their collective ear. He opens the film playing with the film-goer's sensibilities by shooting with bright outdoor lighting and distance shots for positive effect, then abruptly reaches for the dimmer switch once Parker steps onto the island and into the darkened jungle, dropping us right into the middle of Moreau's hell along with Parker. Struss then throws us for a loop every time we see the House of Pain by bathing it in strong light, giving unusual contrast, and a bit of underscore, to the horror that goes on within its walls.

Heading the superb cast is Laughton, who has a field day playing Moreau. His antagonist is equal parts brilliant, mad, pathetic, and contently sadistic. These elements have all be individually realized before by other actors but few have been able to combine them all into one as seamlessly as Laughton does here. As if those layers weren't tough enough to juggle, Laughton even adds seduction to it. In the scenes where Moreau talks of his experiments with Parker, his body language and voice inflection suggests an obsessive need to have Parker understand the doctor's motives even if he cannot accept his actions.

Although portions of H.G. Wells's original novel were jettisoned for the film, screenwriters Waldemar Young and Philip Wylie still deserve much credit for their florid, fresh approach to the material and characters. Each of the players in this tale are shaded with a level of human frailty and depth not always seen in horror films of the period. The best example is the hero Parker, who's engaged to be married and yet has a certain attraction/lust for Lota. This bucks the trend by horror film-makers of the period to portray the hero and heroine of the story as rather dull, chaste types. Though it does serve well to emphasize the scenery-chewing antagonist, it leaves very little room for any fresh change in the good versus evil formula. Here, Parker is just as flawed and interesting of a character as Moreau, providing an extra bit of edginess to the proceedings.

Of course, no character is fully realized without the significant help of some really ripe dialogue, provided here in abundance by Young and Wylie. Some of the best lines come when Parker finds out the creatures can actually speak. "Those poor things out there in the jungle. Those animals. They - they talk." Moreau replies with "That was my first great achievement. Articulate speech controlled by the brain. And it was a great achievement! Oh, it takes a long time and infinite patience to make them talk." Then, in a very droll aside he adds: "Someday I will create a woman and it'll be easier."

Island of Lost Souls is a creepy masterpiece and was a trend-setting early exercise in sadism and perverse cinema horror when released in 1932 that might not have seen the light of day just two years later. It's also surprising to note that not only did the film get released intact when it did, it did so by getting past the real-life monstrosity of puritanism disguised as movie censorship.

Sources:

Bernstein, Matthew. Controlling Hollywood: Censorship and Regulation in the Studio Era. Rutgers University Press, 1999.

Black, Gregory D. Hollywood Censored: Morality Codes, Catholics, and the Movies. Cambridge University Press, 1996.