Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

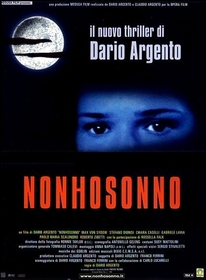

Sleepless (2001)

The serial killer formula is ripe horror fare for film studios looking to grab big money from easy-to-please gorehounds. In fact, the low expectations from slasher film fans provide a perfect excuse for studios to focus less on quality and more on marketing. All a director needs is a flashy look, a decent soundtrack, a lot of blood, and a script that merely serves to connect the gore set-pieces. The problem with Sleepless is that it's directed by a master of suspense films, Dario Argento, and yet still fits the form.

A young boy, Giacomo, witnesses the brutal slaying of his mother at the hands of a dwarf. That murder is one of several that the police in the city of Turin have nicknamed "the Dwarf Killings." With investigators closing in, the killer disappears. Seventeen years later, a new string of slayings have occurred that seem eerily similar to the earlier deaths. The victims are all friends or acquaintances of Giacomo, now a young man working as a waiter in a Japanese restaurant in Rome. He returns to Turin and, with the help of his girlfriend and Moretti, a retired detective who was the lead on the original case, begins his own search for the killer.

The script for Sleepless offers little in the way of surprise for fans of the slasher genre, merely serving as a frame for the murder scenes. As written by Argento, Franco Ferrini and Carlo Lucarelli, the tired script features an abundance of cardboard stereotypes (hero with a traumatic past, guilt-ridden ex-cop, the plucky girlfriend/heroine etc.) and the requisite serial killer plot devices (methodology linked to books/science/religion/victims sharing similar traits, murderer's calling card being left deliberately, the one pattern-breaking murder that gives the cops a new clue). Here, the deaths are connected to a child's nursery rhyme, with paper cutouts of barn animals left near each of the victims' bodies. The one-off death involves a young lady and offers quite a bit of evidence for our heroic trio to use. Argento (with an array of neat twists and original characters on his resume), Ferrini and Lucarelli all seem to be lazily taking a page from the latest Hollywood straight-to-dvd slasher picture.

Still, with all the problems provided by the writers, the film does have a fresh, arty look and a pace to it that carries the film past the story issues. Perhaps writer Argento should thank director Argento for enlivening things and for bringing his box of visual tools. Working with cinematographer Ronnie Taylor, Argento once again brings the camera into the story as an added character of sorts. Whether he uses the lens to show a facial reaction or letting the camera linger a bit on birds or inanimate objects, Argento's visual trickery at once deftly adds to the somber mood of Sleepless and makes the camera a powerful weapon in drawing the filmgoer in. The latter is most evident whenever the killer appears. Argento and Taylor photograph each of the murders from the point of view of the killer. This works because, while the audience is forced to look at events through the eyes of a twisted personality, we get a full view of the looks of sheer terror, shock, and slight resignation on the faces of each victim. These scenes are imbued with an immediacy and, frankly, there are few better, more blunt methods of luring fans in than injecting an urgency to the proceedings.

Much of the fun of Sleepless comes from its at times delirious pace. Though coming in at rather lengthy running time for a thriller, 116 minutes, the film nevertheless is edited with a tone and style befitting a director who has built a career making well-crafted thrillers. There are plenty of action and shocks to keep viewers involved throughout and Argento keenly avoids lulls by eschewing any long exposition or dialogue-heavy scenes. One highlight sequence is a cracking, energetic chase on a train between the psycho and a victim near the film's opening. Mixing the sounds of the train, the heavy breathing of the victim, and a minimum of dialogue, the scene has a frenetic, exciting undertone that sets the bar for the rest of the film.

Further aiding the fast pace of the film is the pulse-pounding music soundtrack created by frequent Argento favorite Goblin. Whenever there's a rare threat of a lull, their highly-charged, often explosive instrumentals ratchet the energy back up. With their at times intense music style and expert usage of the synthesizer, Goblin seems to be a perfect partner for Argento's stark, moody style of filmmaking. This is most evident during the bloody finale, where Giacomo comes face to face with the killer. The section of music used here starts out slow and grows, matching the escalating intensity as events unfold.

If you think about it, Sleepless is that rare film where it's director is both its biggest asset and its major weakness, with a potentially good film suffering somewhere in-between. It's a shame that Argento the director couldn't have had a better creative relationship with Argento the writer this time around. Those two have hit the bullseye on so many previous occasions, one expects it each time they work together.