Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

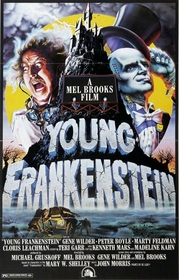

Young Frankenstein (1974)

Some scenes in film history will live in our minds forever. They include the shower scene in Psycho, King Kong on top of the Empire State Building, and the laboratory creation of The Monster in Frankenstein. The visual intensity of those scenes is forever etched in our collective cinematic DNA. Another scene that warrants equal consideration due to its comedic bravura shines in Mel Brooks's spoofy classic Young Frankenstein released in 1974. As The Monster and Dr. Frankenstein's grandson, Frederick, played respectively by Peter Boyle and Gene Wilder, entertain a show hall full of upper-class intellectuals, the duo performs an uncanny version of "Putting on the Ritz". Boyle's performance is legendary, and the image and sound of Frankenstein's Monster in a tuxedo vocalizing his garbled version of the song's title represents one of the funniest scenes in comedy history.

The film deservedly received two Academy Award nominations, one for Best Adapted Screenplay (by Wilder and Brooks) and another for Best Sound, but it won neither. However, that was understandable with such Hollywood heavyweights as Chinatown, The Godfather Part II, and The Conversation standing in the way. Had they not been there, Young Frankenstein might have won at least one Academy Award, an impressive achievement for a horror-laden spoof of the early 70s.

Parodying elements of Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, Son of Frankenstein, and Ghost of Frankenstein, the film features Dr. Frederick Frankenstein, a teaching neurosurgeon and grandson of the legendary Victor Frankenstein. Frederick has spent his life escaping the ignominious shadows of his grandfather, but he inherits his grandfather's castle and finds such a clean escape difficult. There he meets the hunchback Igor (Marty Feldman), a sexy lab assistant named Inga (Teri Garr), and a number of other zany characters who defy logic. Frederick thinks his grandfather's work is junk science, but in the castle, he stumbles upon his diary and learns of his dubious experiments in reanimation. Instantly, Frederick is seduced. He tries to recreate the monster, but the plot thickens when Igor mistakenly retrieves the brain of an abnormal criminal. The Monster is created, but he is not what we expect.

The great cast and acting in Young Frankenstein is remarkable. Brooks's ability to juggle so many disparate talents is clearly demonstrated, as it was in his other classic spoof, Blazing Saddles, also released in 1974. Wilder's comic genius abounds, particularly as he struggles with others' mispronunciation of his name and the manner in which he easily succumbs to the allure of recreating his grandfather's monster. There is something hilarious in seeing hypocrisy unfold, especially when it occurs unknowingly and there is no explanation for it. Even more hilarious is when the hypocrite has spent much time previously denouncing what becomes the hypocritical act. His self-conscious melodrama allows him to perfectly play the victim of others' sarcasm and satire, and he revels in being the target of so many comic arrows.

Feldman arguably steals the show with his appearance, comic asides into the camera, and depraved libido. Garr's quiet sexuality can only be suppressed for so long, and Madeline Kahn, who plays Elizabeth, the Monster's bride, is equally effective in shattering the door to her sexuality's closet. Cloris Leachman and her exaggerated German accent is excellent as the old doctor's housekeeper, and Boyle pulls off one of the more difficult roles in horror history: not only does he adequately portray The Monster and invokes a sense of menace in him, but he gives The Monster a softer credibility and humor, a difficult task when dealing with an archetype. Even Gene Hackman, who plays the blind man that befriends The Monster, makes a memorable appearance. And who can forget Kenneth Mars as Police Inspector Hans Wilhelm Friederich Kemp, whose toy soldier appearance undermines his Nazi-like attitude and whose mechanical arm parodies that famous cinematic cliché used so often, from Peter Sellers in Dr. Strangelove to Bruce Campbell in Army of Darkness.

When Frederick, Igor, and Inga first enter the lab, the voice of Colin Clive, who played the doctor in the original Frankenstein, is heard shouting instructions in the background to help animate The Monster. This point is important because it demonstrates how much of a tribute this film truly is. Like the loving father we love to mock, Brooks clearly loves his Frankenstein films, and by poking fun at them, he also ironically reveals his intimacy with them. Paradoxically, love and sarcasm often go hand-in-hand.

Brooks and the production staff worked diligently to honor the original film's style. In fact, Young Frankenstein was shot in the same castle using the same lab equipment and props used in the 1931 original. Kenneth Strickfaden, the set designer who created the original equipment in James Whale's classic, gave Brooks the rights to use it for this spoof. Shot using exquisite, traditional black and white photography to capture the original's visual essence, Young Frankensten also uses a number of "old-school" transitional devices including irises and swipes to move from scene to scene.

Young Frankenstein's humor is also quite eclectic. The verbal irony crackles on screen: Igor should be pronounced "Eye-Gor", as if we need another reminder of Feldman's eyes; nobody can correctly pronounce Frederick's name; and the brain was thought to be Abby Normal's and not labeled "abnormal". In this classic farce, not even the language is reliable. The humor also moves from slapstick to dramatic irony to deadpan to spoof to burlesque with ease. Furthermore, the absurdity that permeates the film reaches a crescendo that allows us to sympathize with The Monster: wouldn't you feel for someone who was the product of such absurd madness? We sympathize with It because he is not the outsider we have grown accustomed to; here, The Monster seems to belong with this cast of nuts. Strangely, our sympathy surfaces not necessarily because he is an outsider, but because he is too much of an insider. The Monster in Young Frankenstein at times appears to be the most normal member of the cast.

Oozing with sexual innuendo, Young Frankenstein also serves as a metaphor for the sexual revolution of the 60s that infiltrated 70s culture in America. Cast in a Victorian backdrop, the characters appear incongruous while dripping with sexual energy. Their amorous humor reaches its climax at the film's conclusion with allusions to Frederick's exaggerated phallus, the result of a medical transfer that, well, does not go exactly as planned.

But nothing goes as planned in Young Frankenstein, and our expectations should be checked at the door. And that is exactly the point. By mocking the genre's conventions, Brooks & Co. have paid tribute to one of the most endearing characters and series in film history. Thankfully, Young Frankenstein will never get old.