Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

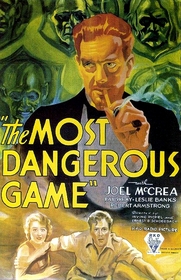

The Most Dangerous Game (1932)

In the 21st century, when just about any kind of sex and violence can be downloaded at the click of a mouse, and torture-packed films such as Saw pull in plenty at the box-office, I often have a tendency to forget how brutal and kinky horror films have always been to some extent, even those made nearly 80 years ago. The Most Dangerous Game is a classic example, a tightly paced mix of cruelty, grisly horror, and deviant sexual desires.

The script stays fairly faithful to the short story by Robert Connell on which it is based, but also adds one detail which subtly adds a new layer to the plot, without losing the straightforwardness that makes the source material so gripping. After his ship is wrecked, world famous big game hunter Robert Rainsford manages to swim to a nearby island. Taking shelter in the castle of the mysterious Count Zaroff, Rainsford meets Eve Trowbridge and her brother Martin, survivors of another wrecked vessel. The guests soon find themselves sucked into the insane games of their host. Zaroff, bored with stalking animals, has decided to go hunting the Most Dangerous Game of all - man...

The film was made in 1932, in the era sometimes known as "Pre-Code Hollywood". At this time, film censorship rules were in place in the form of the Hays Code, the stated aim of which was to ensure that "no picture shall be produced that will lower the moral standards of those who see it", and explicitly banned any depiction or even hint of sexual perversion or "low forms of sex"1. The MPAA adopted the code in 1930, but rarely bothered with it until 1934, when they came under pressure from high profile groups such as the Catholic Legion of Decency. Until then, producers felt that the public were more interested in watching films containing the very things that moral guardians were trying to prevent them from seeing2.

The Most Dangerous Game has sexual undercurrents running through whole of the film, with the first two minutes hinting nicely at what is in store. The opening credits are superimposed over a shot of the front door of Zaroff's castle, with its carved door knocker depicting a frenzied faced Satyr carrying a scantily clad woman in his arms. This same image crops up later in the tapestries adorning Zaroff's wall.

Count Zaroff himself acts as if he is constantly horny, twirling his cigarette in an unsubtly phallic manner and talking like he's constantly on the point of orgasm. His dialogue is peppered with lines such as "kill then love, when you have known that, you have known ecstasy", explicitly stating his belief in the links between violence and sex. The intensity of Banks's performance is helped by a subtle detail I have only recently noticed. While serving in the British army in World War One, he sustained injuries which left one half of his face completely paralyzed.3 This is utilized to great effect in the film, as nearly all scenes where he is playing the charming host are shot with only one side of his face showing to the camera so that you don't see the disparity between his eyes. However, any scene where he is being menacing or lecherous is shot full on, with the injured half of his face having a bulging leering eye that feels as though it could almost pop out of his head at any moment.

A further sexual element is found in the character of Eve Trowbridge, who was not in the original short story. There, the face-off between Rainsford and Zaroff was merely a battle for survival. In the film, while a combination of the brief running time and her character's general passivity leads to her not making a massive impression beyond her looks, her mere existence means that the duel now takes on an air of two animals fighting for possession of a mate. When Zaroff, just before loosing his guests into the forest to be hunted, says that "...one does not kill the female", the implication (bearing in mind he prefers to "kill, then love") is that after capturing and murdering Rainsford, he intends to rape Eve.

But enough about sex, what about the horror? While the film stays close to its literary source material as far as plot goes, for nearly every other aspect (shot composition, cinematography, dialogue, production design, and acting style) it draws heavily on the tradition of "Grand Guignol". This means4 dispensing, at least on the surface, with subtlety and playing up the gruesomeness of the subject matter, the distorted viewpoints of the characters, their cruelty and sadism. Therefore we get lots of ripe dialogue from Zaroff (when he offers to "take care" of Eve's brother, we all know what's really going to happen) as well as sweeping tracking shots leading to bulging eyed facial expressions in close up, and a score that doesn't hold back on volume and pace, especially during the chase sequences. "Grand Guignol" also dispenses with the supernatural, in favor of the horror that man can inflict on his fellow man or as the philosopher Noël Carroll said "though gruesome, Grand-Guignol requires sadists rather than monsters."5 This is summed up perfectly in the scene where Eve and Rainsford discover Zaroff's trophy room, which consists entirely of human heads, both mounted on the wall and floating in glass tanks, their mouths frozen forever in permanent silent screams. These aren't needed for black magic rituals or pseudo-scientific experiments. This is purely Zaroff boasting of his ability to hunt and kill his fellow human beings.

As is sometimes the case (Bela Lugosi's Dracula or Jack Nicholson's Joker spring to mind), the bad guy far outshines the good guy, both in complexity of character, sex appeal and charisma, and the film does not really spring into life until Zaroff appears. With his complete lack of empathy towards the human beings he murders, he is the progenitor of all those slasher movie maniacs to come, although his intelligence and cunning rationalization of his actions (as well as his suaveness and initial charm) make him more Hannibal Lecter than Michael Myers. He clearly does not see what he does as murder, but as a game (which perhaps gives the film's title an interesting double meaning as well) with strict rules to abide by, and it seems perfectly plausible that he would let people go if they survived his pursuit.

So what about our hero? Rainsford is no square-jawed Flash Gordon type. Although he is just as genuine as Zaroff in his love of hunting animals, having written many books on the subject (Zaroff has read them all, naturally), he clearly feels no empathy for his prey, feeling that they enjoy being hounded to their deaths. However, here he is given the chance to find out how the hunted feels, and despite his initial qualms about taking human life he soon learns that if he is going to get off the island alive, there is no room for nobility, and he is going to have to be as vicious and ruthless as the hunter.

But aside from the more explicit subject matter in the film, there is a second, more subtly chilling strand of horror at work here. If the thrill of the chase is the one thing that keeps Zaroff going, then the realization that he is bored of it has pushed him over the edge into insanity. In other words, he is having something of an existential crisis. The theme of existence and its meaning or meaninglessness is a vital part of the horror genre. Dracula explored the horror of living forever, Frankenstein the horror of being born without being asked (as well as the consequences for the "parents"). Here Zaroff is up against a classic paradox; if our goals and ambitions are the only things that give our life meaning, what do we do when we achieve them? Should we set more goals and ambitions? But what about when we have achieved those? How many fresh goals can we set? And what if we don't achieve those? Does that make us failures? The Most Dangerous Game did not provide any easy answers, but, having watched it countless times over the years, it has always left me with plenty to think about.

Many people have remade the story officially, such as in Robert Wise's A Game of Death (1945) and many, many more have ripped it off (Bloodlust, The Woman Hunt, Turkey Shoot, and Surviving the Game to name a few). Some are more successful than others but none of the versions I have seen pack anywhere near the kind of punch, and capture the sense of sexually charged violence and madness that The Most Dangerous Game does.

This review is part of our Shocktober Classics 2009: Staff Screams event.

1 "The Motion Picture Production Code of 1930 (Hays Code)." ArtsReformation.com. Updated 12 April 2006. Retrieved 05 October 2009.

2 Hunt, Paula. "Sex and Politics: Mixed Reviews." MovieMaker.com. Published 02 September 1999. Retrieved 05 October 2009.

3 Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 05 October 2009.

4 Hand, Richard J. and Michael Wilson. "The Grand-Guignol: Aspects of Theory and Practice." Theatre Research International. Autumn 2000: 266-275. Available online at GrandGuignol.com.

5 Carroll, Noël. "The Philosophy of Horror, or, Paradoxes of the Heart." Routledge, 1990. Page 15.

Trivia:

As well as sharing sets with King Kong, The Most Dangerous Game used many of the same cast (Fay Wray, Robert Armstrong, Noble Johnson, and Steve Clemente) and crew (producer Merian C. Cooper, co-director Ernest B. Schoedsack, editor Archie E. Marshek, composer Max Steiner and screenwriter James Ashmore Creelman).

Noble Johnson was actually African American and plays Zaroff's manservant Ivan in "whiteface".

The trophy room scene was reportedly much longer in the original version of the film with Zaroff giving a guided tour of his museum. However, weak stomached preview audiences began heading for the door, so it was cut back to the length we have now. None of this footage is known to have survived. (Source: IMDb)