Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

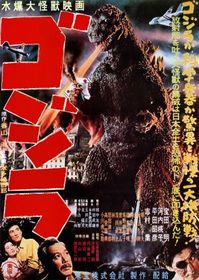

Gojira (1954)

For his size, Godzilla certainly gets around, having attained a certain pop cultural ubiquity in the fifty-five years since his creation. He's been the star of several dozen Japanese films, an American remake, video games, comic books, cartoons, shoe commercials and even a series of novels for young adults. Godzilla references also pop up in sources ranging from the Friday the 13th series to The Simpsons. However, in his debut in Ishiro Honda's Gojira (1954), Godzilla is not a lovable icon, but a solemn and powerful force of devastation - a far cry from the image we have of him today. Ironically, it is in this film that Godzilla is at his most effective.

Japanese fishing boats are mysteriously disappearing in the middle of the sea, befuddling government officials. When one survivor washes up on Odo Island, a group of scientists go to investigate, only to discover that the culprit behind the attacks on the boats is a giant radioactive lizard. Professor Yamane (Takashi Shimura) wants to study the creature, dubbed Gojira, but the authorities want to destroy it. One solution for stopping the monster may rest with a discovery made by Dr. Serizawa, a brilliant scientist who is determined not to add a new weapon the world’s arsenal. Complicating matters is the fact that he is engaged to Yamane's daughter, Emiko (Momoko Kochi) who is in love with another man, Hideto (Akira Takarada). As Gojira's rampage brings destruction and death to the heart of Tokyo, Serizawa and Emiko are faced with difficult choices that may affect the fate of mankind.

Director and co-writer Ishiro Honda, who had been deeply affected by a trip through the ruins of Hiroshima shortly after World War II ended, intended Gojira as a warning against the proliferation of nuclear weaponry. There has been extensive critical examination of the effectiveness of his message and Godzilla as a metaphor for the atom bomb elsewhere, and I'm not interested in rehashing the same material. Instead, I'll point you to the two chapters on Gojira in David Kalat's A Critical History and Filmography of Toho's Godzilla Series (McFarland Press, 1997).

Honda's masterful work as a director in Gojira, however, deserves all the recognition it can get it. Observe how he handles the scenes directly after Godzilla's most destructive rampage, beginning with the most affecting moment in the whole film – a single pan across the rubble-laden ruins of Tokyo. With that one shot, Honda manages to express the cost of the nuclear devastation that Godzilla represents – the homes lost, the businesses obliterated, the communities crushed. Then, to put an exclamation mark – or several – on his statement, Honda brings us to the hospital where the injured and dying overwhelm the available space, with bedrolls laid out on the floor of every room, every hallway. Here we watch a little girl diagnosed with fatal radiation poisoning, while another girl watches her dead mother carted away. Throughout this sequence, Honda walks a fine line between simply recording the scene and becoming part of it.He uses documentarian long takes, but his camera seems drawn towardsthe unfortunate disaster victims. The overall effect is one of someone struggling to record the events without getting involved - and only partially succeeding.

With the interpersonal drama surrounding the Yamanes and Dr. Serizawa, Honda moves more fully into subjective, expressionist filmmaking. When Dr. Yamane is despondent over plans to destroy Godzilla, he isn't the only thing displaying a black mood – his office is cloaked in darkness, save for a few dim key lights that call attention to the scientist's exquisitely pained face. Later in the movie, when Dr. Serizawa makes a painful decision, a close-up on Emiko at the verge of tears suddenly jump cuts to her falling out of frame with uncontrolled sobbing. Its a split-second, but it says everything about Emiko's state of mind – her sorrow is so powerful that it skips all interceding emotions.1

Honda and co-writer Takeo Murata provide one of the sturdiest narratives to ever grace the “giant monster on the loose” genre. All of the characters fit together logically, with very little coincidence binding them together. The Serizawa/Emiko/Hideto love triangle adds an additional layer of human drama that underscores and intensifies each characters' involvement with Godzilla's destructive rampage. When Serizawa becomes aware that Emiko, the woman he loves, the person asking him to betray his principles in order to end the the threat of Godzilla, is in love with another, his ideological conflict becomes a personal one as well. Likewise, these factors add an important emotional depth to hid eventual decision, which allows the film to amp up its dramatic momentum in its exciting finale.

There's a story about how actor Akira Takarada showed up on set and introduced himself as the star of the film, only to be rebuffed by the crew, who pointed out that the real star was Godzilla. It's an amusing tale, but the crew had it wrong. Godzilla is no more the star here than the tidal wave in The Poseidon Adventure. He's a force of nature that requires a human reaction and the cast of Gojira supplies that wonderfully. In particular, Takashi Shimura, a favored actor of Akira Kurosawa, adds great depth as Dr. Yamane. His lined face is a perfect vehicle for the internal conflict between the scientist who wants to study Godzilla and the man who despairs at the human casualties the monster causes.

Special effects director Eiji Tsuburaya originally wanted to use classic stop-motion animation a la King Kong to portray Godzilla, but time and budget limitations forced a different solution on him: men in monster suits. Despite this setback, Tsuburaya's effects work is impressive. The scale sets of Tokyo that he and his team built for Godzilla to wreak havoc upon are crafted with real attention to detail, not only in appearance but also in the general construction. It is not enough for a building to be toppled for Tsuburaya and his team; it must topple in exactly the same manner that the full-size building would. The reality they construct is so convincing, in fact, that some of the effects they employ don't even appear to be effects at all. For instance, in one sequence, we are shown cars driving past the bases of a massive electrical fence. Those bases are matted into the shot, but they look like completely natural parts of the scene.

Many of the sequels that have followed Gojira are classics in their own right, but none will match the emotional depth and amazing storytelling on display in this, our first introduction to the monster known as Godzilla. A combination of a well-developed storyline, somber mood, great direction, strong acting, and impressive special effects allow this to be perhaps the greatest of all Japanese monster movies. The legacy continues, but the legend will never be greater than he was in 1954.

Part of Godzilla Week, a crossover event with The Sci-Fi Block. Read the SFB review of Gojira.

- 1. What's particularly interesting about this edit, though, is that this particular use of the jump cut didn't rise to prominence until the onset of the French New Wave in the late 1950s. Honda's application of it here appears to be something of a prescient anomaly.